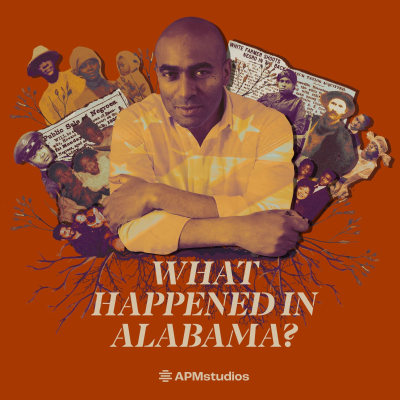

What Happened In Alabama?

English

Documentary

Limited Offer

2 months for 19 kr.

Then 99 kr. / monthCancel anytime.

- 20 hours of audiobooks / month

- Podcasts only on Podimo

- All free podcasts

About What Happened In Alabama?

What Happened in Alabama? is a series born out of personal experiences of intergenerational trauma, and the impacts of Jim Crow that exist beyond what we understand about segregation. Through intimate stories of his family, coupled with conversations with experts on the Black American experience, award-winning journalist Lee Hawkins unpacks his family history and upbringing, his father’s painful nightmares and past, and goes deep into discussions to understand those who may have had similar generational - and present day - experiences. What Happened In Alabama? is a series to end the cycles of trauma for Lee, for his family, and for Black America.

All episodes

16 episodesAction and Accountability

Real estate accounts for 18% GDP and each home sale generates two jobs. It’s a top priority for state officials and business leaders across the country to build stable communities. In Minnesota, efforts to address inequity that keeps people locked out of the property market are well-advanced. Lee sits down to interview those directly involved. TRANSCRIPT Part 3 – Action and Accountability LT GOV PEGGY FLANAGAN: An apology is powerful. But in the same way that I think things like land acknowledgements are powerful. If you don't have policies and investments to back them up, then they're simply words. You’re listening to Unlocking The Gates, Episode 3. My name is Lee Hawkins. I’m a journalist and the author of the book I AM NOBODY’S SLAVE: How Uncovering My Family’s History Set Me Free. I investigated 400 years of my Black family’s history—how enslavement and Jim Crow apartheid in my father’s home state of Alabama, the Great Migration to St. Paul, and our move to the suburbs shaped us. Community and collaboration are at the heart of this story. I’ve shared deeply personal accounts, we’ve explored historical records, and everyone we’ve spoken to has generously offered their memories and perspectives. Jackie Berry is a Board Member at Minneapolis Area Realtors. She’s been working to address the racial wealth gap in real estate. And she says; JACKIE BERRY: We need to do better. We have currently, I think it's around 76% of white families own homes, and it's somewhere around 25-26% for black families. If we're talking about Minnesota, in comparison to other states, we are one of the worst with that housing disparity gap. And so, it's interesting, because while we have, while we make progress and we bring in new programs or implement new policies to help with this gap, we're still not seeing too big of a movement quite yet. Jackie says there’s a pretty clear reason for this. JACKIE BERRY: Racial covenants had a direct correlation with the wealth gap that we have here today. Okay, if you think about a family being excluded from home ownership, that means now they don't have the equity within their home to help make other moves for their family, whether it's putting money towards education or by helping someone else purchase a home or reducing debt in other areas in their life. Racial covenants were not just discriminatory clauses—they were systemic barriers that shaped housing markets and entrenched inequality. LT GOV PEGGY FLANAGAN In my community of St Louis Park, there is, you know, there are several racial covenants. You know, our home does not have one, fortunately. Lieutenant governor Peggy Flanagan is the highest ranking Native American female politician in the country. I asked her about her experience and how it informs her leadership. LT GOV PEGGY FLANAGAN: I can tell you that I never forget that I'm a kid who benefited from a section eight housing voucher, and that my family buying a home made a dent in that number of native homeowners in this state, and I take that really seriously, LEE HAWKINS: You know? And it's powerful, because I relate to you on that. You know, this series is about just that, about the way that the system worked for a group of people of color who were just doing what everyone else wants to do, is to achieve the American Dream for their children. And so I see you getting choked up a little bit about that. I relate to that, and that's what this series is about. Homeownership is more than a marker of personal achievement—it’s a cornerstone of the U.S. economy. Real estate accounts for 18% of GDP, and each home sale generates two jobs. This is why state officials and business leaders continue to prioritize stable and thriving communities. Remember earlier in the series we spoke about some other influential men in the state who were involved in creating the housing disparity gap that we have today. LT GOV PEGGY FLANAGAN: I don’t believe that that Thomas Frankson ever imagined that there would be an Ojibwe woman as lieutenant governor several, several years after he was in this role, and additionally, right? It’s symbolic, but also representation without tangible results, right? Frankly, doesn’t, doesn’t matter. And so, I think acknowledging that history is powerful. I think it has to do with how we heal and move forward. And we can’t get stuck there. MARGARET THORPE-RICHARDS: Thorpe Brothers was very much a part of my childhood and sort of upbringing. But my own father, Frank Thorpe, was not part of the real estate business. He chose to do investments. This is Margaret Thorpe-Richards. Her grandfather is Samuel Thorpe. Head of Thorpe Brothers, the largest real estate firm in Minneapolis, which he helped establish in 1885. I asked her to share her memories. MARGARET THORPE-RICHARDS: My uncle, my dad's brother, Sam Thorpe, the third, also followed in the Thorpe Brothers family business and he ran it until kind of that maybe the early 80s or mid 80s. But anyway, they sold off the residential to another big broker here, and then just kept commercial. While I was growing up you know I was aware about real estate but not actively involved. MARGARET THORPE-RICHARDS: Both my grandfather and grandmother, they were very much, I don't know, white upper class, you know, I remember going to dinner at their house, they weren't very reachable, like personally, so I never really had a relationship with them, even though they lived two or three doors down. And that's kind of my recollection. LEE HAWKINS: Okay. And so, at that time, there was no indication that there was any racism in their hearts or anything like that. MARGARET THORPE-RICHARDS: Oh, I don't know if I want to say that. Margaret’s entry into the real estate business didn’t happen in the way you might expect given her grandfather’s outsized role in the industry. MARGARET THORPE-RICHARDS: I went to my uncle Sam who was at the helm of Thorpe Brothers Real Estate it was still intact and he didn't see the opportunity or the talent that I had which I have to say I always have had I'm not going to be boastful but I'm really good at sales and so he never he never explored that and I think basically that was sexism. We didn't really have a great relationship. My father died early. He died when I was 18. So that also impacted things. It was my mother who's not the blood relative, Mary Thorpe Mies. She went into real estate during kind of the boom years of 2000. She said you need to come. She said, I'll help you get started." And we had a good long run for probably 10 years and then she retired, and I've been on my own until a year and a half ago when my oldest son Alexander joined me as my business partner. So now we're the Thorpe Richards team and he is essentially fifth generation realtor of the Thorpe family. The nature of her family’s role in the origins of discriminatory housing policy is a recent discovery for Margaret and her two sons. MARGARET THORPE-RICHARDS: I really didn't know about these covenants until it was 2019 when, and I was actually on the board of the Minneapolis Area Association of Realtors I asked her how she felt when she found out. MARGARET THORPE-RICHARDS: I was horrified. It felt shameful. I'm not going to fix anything, but I would like to show up in a way that says I think this was wrong and I'd like to help make it right. I felt like I needed to take some ownership. I also was a little worried about putting a stain on the Thorpe name by sort of speaking my truth or what I feel we have a huge family. So I was reluctant maybe to speak out against, you know, the wrongs. However, I've just been trying to do my job at educating and being welcoming and creating it as part of our mission that we want to, you know, serve those who have not been well -served and have been discriminated and who've had an economic hardship because of the way that things were. I can relate to what Margaret is saying here. MARGARET THORPE-RICHARDS: And that has proven to be challenging as well. I'm not gonna lie. I'm white. I'm not black. So, how do I sort of reach over to extend our expertise and services to a population that maybe wants to deal with somebody else who's looks like them or I don't know it's a tricky endeavor and we continue to try and do outreach. I went through a similar range of emotions and thoughts while writing my book and uncovering family secrets that some of my relatives would rather not to think about. It led to some difficult discussions. I asked her if she’d had those conversations with her family - MARGARET THORPE-RICHARDS: Mm -mm. This might be it, Lee. This could be the conversation. I feel like it's time to say something from my perspective. I have a platform, I have a voice, and I think it needs to be said and discussed and talked about, One thing that struck me in my conversation with Margaret is her advanced-level understanding of the issue. She mentioned the challenge of foundational Black Americans versus immigrants. Families who moved from the South looking for opportunities after World War one and two were most severely affected by these discriminatory policies. Here’s Jackie Barry Director of Minneapolis Area Realtors; JACKIE BERRY: Between 1930 and 1960 and to me, this is a staggering statistic, less than 1% of all mortgages were granted to African Americans across the country. That truly speaks to having a lack of equity to pull out of any homes, to be able to increase wealth and help other family members. Efforts to address this are well-advanced here. Yet, lieutenant governor Flanagan is clear about how much more can and should be done LT GOV PEGGY FLANAGAN: It's important to acknowledge and to provide folks with the resources needed to change and remove those covenants, which is a whole lot of paperwork, but I think is worth doing. And then figure out, how do we make these investments work? In partnership with community. I asked why the state has not issued an official apology for its role in pioneering structural housing discrimination and whether she sees any value in doing so. LT GOV PEGGY FLANAGAN: An apology is powerful. But in the same way that I think things like land acknowledgements are powerful. If you don't have policies and investments to back them up, then they're simply words. So I think the work that we have done during our administration, is one of the ways that we correct those wrongs, explicitly apologizing. I think could be something that is is powerful, and I don't want us to just get stuck there without doing the actual work the people expect of us. I wanted to understand what that work is – LT GOV PEGGY FLANAGAN: I think when we increase home ownership rates within our communities, it's a benefit to the state as a whole, LEE HAWKINS: right, okay, so not necessarily going back and doing reparatory justice, but looking out into the future. LT GOV PEGGY FLANAGAN: But I think that is reparatory justice, okay, making those investments in communities that have been historically underserved, you know, partnering with nonprofits that are led by and for communities of color, that are trusted. I asked all three women for their thoughts on the pace of progress. Here’s Margaret – MARGARET THORPE-RICHARDS: I don't see it changing very quickly. So I don't know how to sort of fuel that effort or movement. It seems like we talk about it a lot, yet the needle isn't moving. And Jackie - JACKIE BERRY: We need to increase our training and development. So in Minnesota, a realtor has to do um complete Fair Housing credits every two years, meaning that they're getting some type of education related to learning about housing discrimination and how to avoid it, how to represent clients equitably, understanding rules and regulations around fair housing. And lieutenant governor Flanagan LT GOV PEGGY FLANAGAN: Our legislation that we passed in 2023 was $150 million directed at first time homebuyers and black, indigenous and communities of color. We see that, I think, as a down payment right on the work needs to happen. The legislature is the most diverse legislature we've ever had, three black women who are elected to the Senate, the very first black women ever to serve. And I think we start to see the undoing of some of that injustice simply because there are more of us at the table. Communicating these complex policies and ideas is no easy task at the best of times. I was talking to the lieutenant governor shortly after the 2024 presidential election which delivered a stinging rebuke of the Democratic party and many of the social justice initiatives it champions. LT GOV PEGGY FLANAGAN: Listen, I'm a Native American woman named Peggy Flanagan, I've been doing this dance my entire life, right? And, you know. I also know that Minnesotans really care about their neighbors. They really care about their communities and the state, and frankly, people are sick and tired of being told that they have to hate their neighbor. We're over it. LEE HAWKINS: What do you say to them when they say that's woke and I'm tired of it. I'm fatigued. I didn't do anything, I didn't steal land, I didn't enslave people, and I'm feeling attacked. LT GOV PEGGY FLANAGAN: The biggest thing that we need to do right now, is just, is show up and like, listen and, you know, find those common values and common ground. LEE HAWKINS: And this doesn't have to be a partisan conversation. LT GOV PEGGY FLANAGAN: It does not, and frankly, it shouldn't be. LEE HAWKINS: Have you seen that kind of that kind of cooperation between the parties in Minnesota here with it's actually some of these reparations’ measures could be doable. LT GOV PEGGY FLANAGAN: I don't know that they say reparations, but I would say LEE HAWKINS: It's a very polarizing word to some extent. LT GOV PEGGY FLANAGAN: Everything that we do has to be grounded in relationships Throughout this series, we’ve explored the legacies of Frank and Marie Taurek, who embodied allyship and fairness by making land accessible to Black families. James and Frances Hughes, built on that opportunity, fostering collaboration within the Black community by creating pathways to homeownership. These families, in their own ways, represent the power of choice: to open doors, to challenge norms, and to plant seeds of progress. Their stories remind us that even within deeply flawed systems, individuals can make decisions that echo across generations. But as we reckon with the enduring impacts of housing discrimination and inequity, the question remains: In our time, what choices will we make to move forward—and who will they benefit? You’ve been listening to Unlocking the Gates: How the North led Housing Discrimination in America. A special series by Marketplace APM with research support from the Alicia Patterson Foundation and Mapping Prejudice. You’ve been listening to Unlocking the Gates: How the North led Housing Discrimination in America. A special series by APM Studios AND Marketplace APM with research support from the Alicia Patterson Foundation and Mapping Prejudice. Hosted and created by me, Lee Hawkins. Produced by Marcel Malekebu and Senior Producer, Meredith Garretson-Morbey. Our Sound Engineer is Gary O’Keefe. Kelly Silvera is Executive Producer.

The Perpetual Fight

Racial covenants along with violence, hostility and coercion played an outsized role in keeping non-white families out of sought after suburbs. Lee learns how these practices became national policy after endorsement by the state’s wealthy business owners and powerful politicians. TRANSCRIPT Part 2 – Discrimination and the Perpetual Fight Cold Open: PENNY PETERSEN: He doesn't want to have his name associated with this. I mean, it is a violation of the 14th Amendment. Let's be clear about that. So he does a few here and there throughout Minneapolis, but he doesn't record them. Now, deeds don't become public records until they're recorded and simultaneously, Samuel Thorpe, as in, Thorpe brothers, is president of the National Board of Real Estate FRANCES HUGHES (ACTOR): “Housing for Blacks was extremely limited after the freeway went through and took so many homes. We wanted to sell to Blacks only because they had so few opportunities.” LEE HAWKINS: You know, all up and down this street, there were Black families. Most of them — Mr. Riser, Mr. Davis, Mr. White—all of us could trace our property back to Mr. Hughes at the transaction that Mr. Hughes did. CAROLYN HUGHES-SMITH: What makes me happy is our family was a big part of opening up places to live in the white community. You’re listening to Unlocking The Gates, Episode 2. My name is Lee Hawkins. I’m a journalist and the author of the book I AM NOBODY’S SLAVE: How Uncovering My Family’s History Set Me Free. I investigated 400 years of my Black family’s history — how enslavement and Jim Crow apartheid in my father’s home state of Alabama, the Great Migration to St. Paul, and our move to the suburbs shaped us. We now understand how the challenges Black families faced in buying homes between 1930 and 1960 were more than isolated acts of attempted exclusion. My reporting for this series has uncovered evidence of deliberate, systemic obstacles, deeply rooted in a national framework of racial discrimination. It all started with me shining a light on the neighborhood I grew up in – Maplewood. Mrs. Rogers, who still lives there, looks back, and marvels at what she has lived and thrived through. ANN-MARIE ROGERS: My kids went to Catholic school, and every year they would have a festival. I only had the one child at the time. They would have raffle books, and I would say, don’t you dare go from door to door. I family, grandma, auntie, we'll buy all the tickets, so you don't have to and of course, what did he do? And door to door, and I get a call from the principal, Sister Gwendolyn, and or was it sister Geraldine at that time? I think it was sister Gwendolyn. And she said, Mrs. Rogers, your son went to a door, and the gentleman called the school to find out if we indeed had black children going to this school, and she said, don’t worry. I assured him that your son was a member of our school, but that blew me away. In all my years in Maplewood, I had plenty of similar incidents, but digging deeper showed me that the pioneers endured so much more, as Carolyn Hughes-Smith explains. CAROLYN HUGHES-SMITH: The one thing that I really, really remember, and it stays in my head, is cross burning. It was a cross burning. And I don't remember exactly what's it on my grandfather's property? Well, all of that was his property, but if it was on his actual home site. Mrs. Rogers remembers firsthand – ANN-MARIE ROGERS: I knew the individual who burned the cross. Mark Haynes also remembers – MARK HAYNES: phone calls at night, harassment, crosses burned In the archives, I uncovered a May 4, 1962, article from the St. Paul Recorder, a Black newspaper, that recounted the cross-burning incident in Maplewood. A white woman, Mrs. Eugene Donavan, saw a white teen running away from a fire set on the lawn of Ira Rawls, a Black neighbor who lived next door to Mrs. Rogers. After the woman’s husband stamped out the fire, she described the Rawls family as “couldn’t be nicer people.” Despite the clear evidence of a targeted act, Maplewood Police Chief Richard Schaller dismissed the incident as nothing more than a "teenager’s prank." Instead of retreating, these families, my own included, turned their foothold in Maplewood into a foundation—one that not only survived the bigotry but became a catalyst for generational progress and wealth-building. JESON JOHNSON: when you see somebody has a beautiful home, they keep their yard nice, they keep their house really clean. You know that just kind of rubs off on you. And there's just something that, as you see that more often, you know it just, it's something that imprints in your mind, and that's what you want to have, you know, for you and for your for your children and for their children. But stability isn’t guaranteed. For many families, losing the pillar of the household—the one who held everything together—meant watching the foundation begin to crack. JESON JOHNSON: if the head of a household leaves, if the grandmother that leaves, that was that kept everybody kind of at bay. When that person leaves, I seen whole families just, just really go downhill. No, nobody's able to kind of get back on your feet, because that was kind of the starting ground, you know, where, if you, if you was a if you couldn't pay your rent, you went back to mama's house and you said to get back on your feet. For Carolyn Hughes-Smith, inheriting property was a bittersweet lesson. Her family’s land had been a source of pride and stability— holding onto it proved difficult. CAROLYN HUGHES-SMITH: We ended up having to sell it in the long run, because, you know, nobody else in the family was able to purchase it and keep going with it. And that that that was sad to me, but it also gave me an experience of how important it is to be able to inherit something and to cherish it and be able to share it with others while it's there. Her family’s experience illustrates a paradox—how land, even when sold, can still transform lives. CAROLYN HUGHES-SMITH: Us kids, we all inherited from it to do whatever, like my brother sent his daughter to college, I bought some property, you know? But not all families found the same success in holding onto their homes. For Mark Haynes, the challenges of maintaining his father’s property became overwhelming, and the sense of loss lingered. MARK HAYNES: it was really needed a lot of repair. We couldn't sell it. It was too much. It wasn't up to code. We couldn't sell it the way it was. Yes, okay, I didn't really want to sell it. She tried to fix it, brought up code, completely renovated it. I had to flip I had to go get a job at Kuhlman company as a CFO, mm hmm, to make enough money. And I did the best I could with that, and lost a lot of money. And LEE HAWKINS: Oh, gosh, okay. So when you think about that situation, I know that you, you said that you wish you could buy it back. MARK HAYNES: Just, out of principle, it was, I was my father's house. He, he went through a lot to get that and I just said, we should have it back in the family. For Marcel Duke, he saw the value of home ownership and made it a priority for his own life. MARCEL DUKE: I bought my first house when I was 19. I had over 10 homes by time I was 25 or 30, by time I was 30 This story isn’t just about opportunity—it’s about the barriers families had to overcome to claim it. Before Maplewood could become a community where Black families could thrive, it was a place where they weren’t even welcome. The racial covenants and real estate discrimination that shaped Minnesota’s suburban landscape are stark reminders of how hard-fought this progress truly was. LEE HAWKINS: I read an article about an organization called Mapping Prejudice which identifies clauses that say this house should never be sold to a person of color. So we had this talk. Do you remember? PENNY PETERSEN: I certainly do, it was 2018. Here’s co-founder Penny Petersen. PENNY PETERSEN: So I started doing some work, and when you you gave me the name of Mr. Hughes. And I said, Does Mr. Hughes have a first name? It make my job a lot easier, and I don't think you had it at that point. So I thought, okay, I can do this. LEE HAWKINS: I just knew it was the woman Liz who used to babysit me. I just knew it was her grandfather. PENNY PETERSEN: Oh, okay, so, he's got a fascinating life story. He was born in Illinois in. He somehow comes to Minnesota from Illinois at some point. And he's pretty interesting from the beginning. He, apparently, pretty early on, gets into the printing business, and eventually he becomes what's called an ink maker. This is like being a, you know, a chemist, or something like, very serious, very highly educated. In 1946 he and his wife, Francis Brown Hughes and all. There's a little more about that. Bought 10 acres in the Smith and Taylor edition. He tried to buy some land, and the money was returned to him when they found it. He was black, so Frank and Marie Taurek, who maybe they didn't like their neighbors, maybe, I don't know. It wasn't really clear to me, PENNY PETERSEN: Yeah, yeah. And so maybe they were ready to leave, because they had owned it since 1916 so I think they were ready to retire. So at any rate, they buy the land. They he said we had to do some night dealing, so the neighbors didn't see. And so all of a sudden, James T Hughes and Francis move to Maplewood. It was called, I think in those days, Little Canada, but it's present day Maplewood. So they're sitting with 10 acres of undeveloped land. So they decide we're going to pay it off, and then we'll develop it. Hearing Penny describe Frank Taurek takes me back to the conversation I had with his great granddaughter Davida who never met him and only heard stories that didn’t paint him in the most flattering light. DAVIDA TAUREK: It feels like such a heroic act in a way at that time and yet that's not, it seems like that's not who his character was in on some levels, you know. HAWKINS: But people are complicated The choices made by Frank and Marie Taurek—choices that set the stage for families like mine—are reflected in how their descendants think about fairness and equity even today. That legacy stands alongside the extraordinary steps taken by James and Frances Hughes. Penny Petersen explains how they brought their vision to life. PENNY PETERSEN: They paid it off in a timely fashion. I think was 5% interest for three years or something like that. He plaits it into 20 lots, and in 1957 he starts selling them off. And he said there were one or two white families who looked at it, but then decided not to. But he he was had very specific ideas that you have to build a house of a certain, you know, quality. There were nice big lots, and the first family started moving in. So that's how you got to live there. But interestingly, after the Hughes bought it in 1946 some a guy called Richard Nelson, who was living in Maplewood, started putting covenants around it. LEE HAWKINS: There were people who were making statements that were basically explicitly excluding Negroes from life liberty and happiness. And these are big brands names in Minnesota. One was a former lieutenant governor, let's just put the name out there. Penny explains how we got here: PENNY PETERSEN: The first covenant in Hennepin County and probably the state of Minnesota, seems to be by Edmund G Walton. He lived in Minneapolis in 1910 he enters a covenant. He doesn't do it. This is great because his diaries are at the Minnesota Historical Society. He was, by the way, born in England. He'd never he may or may not have become an American citizen. He was certainly voting in American presidential elections. He was the son of a silk merchant wholesaler, so he was born into money. He wasn't landed gentry, which kind of chapped him a lot. And he he came to America to kind of live out that life. So he he's casting about for what's my next, you know, gig. And he goes through a couple things, but he finally hits on real estate. And he He's pretty good at it. He's, he's a Wheeler Dealer. And you can see this in his letters to his mom back in England, in the diaries, these little, not so maybe quite legal deals he's pulling off. But by, by the early aughts of the 20th century, he's doing pretty well, but he needs outside capital, and so he starts courting this guy called Henry or HB Scott, who is land agent for the Burlington railroad in Iowa, and he's immensely wealthy. And. No one knows about Henry B Scott in Minneapolis. You know, he's some guy you know. So he gets Scott to basically underwrite this thing called what will be eventually known as Seven Oaks Corporation. But no one knows who he is really what Edmund Walton does so he gets, he gets this in place in 1910 Walton, via Henry Scott, puts the first covenant in. And there's a laundry list of ethnicities that are not allowed. And of course, it's always aimed at black people. I mean that that's that's universal. And then what's happening in the real estate realm is real estate is becoming professionalized. Instead of this, these guys just selling here and there. And there's also happening about this time, you know, race riots and the NAACP is formed in 1909 the Urban League in 1910 and I think Walton is he sees something. I can make these things more valuable by making them White's only space. But he doesn't want to have his name associated with this. I mean, it is a violation of the 14th Amendment. Let's be clear about that. So he does a few here and there throughout Minneapolis, but he doesn't record them. Now, deeds don't become public records until they're recorded and simultaneously, Samuel Thorpe, as in, Thorpe brothers, is president of the National Board of Real Estate, you know, and he's listening to JC Nichols from Kansas City, who said, you know, a few years ago, I couldn't sell a lot with covenants on them, but now I can't sell it without covenants. After that, that real estate convention, there's one in 1910 and Walton is clearly passing this around, that he's he's put covenants in, but no one really talks about it, but they you know, as you look back when the deeds were signed, it's like 1910 1911 1912 the 1912 one when HB, when JC, Nichols said, I can't sell a lot without him. Sam Thorpe immediately picks up on this. He's the outgoing president of the National Board of Real Estate. By June, by August, he has acquired the land that will become Thorpe Brothers Nokomis Terrace. This is the first fully covenanted edition. He doesn't record for a while, but within a few years, they're not only these things are not only recorded, but Walton is advertising in the newspaper about covenants, so it's totally respectable. And then this is where Thomas Frankson comes in. In Ramsey County, he's still in the legislature when he puts his first covenant property together, Frankson Como Park, and in 1913 he's advertising in the newspapers. In fact, he not only advertises in English, he advertises in Swedish to let those Swedish immigrants know maybe they don't read English. So well, you can buy here. This will be safe. Penny says the National Board of Real Estate but she means the National Association of Realtors. Samuel Thorpe was not only the President of this powerful organization, he even coined the term ‘realtor’ according to records. I want to take a moment to emphasize that Thomas Frankson is a former lieutenant governor. They were architects of exclusion. By embedding racial covenants into the fabric of land deals, they set a legal precedent that shaped housing markets and defined neighborhoods for decades. As Penny Petersen noted, these practices were professionalized and legitimized within the real estate industry. Michael Corey, Associate Director of Mapping Prejudice explains how these covenants were enforced. MICHAEL COREY: And so in the newspaper, as not only do they put the text of the Covenant, then two lines later, it says, you have my assurance that the above restrictions will be enforced to the fullest extent of the law. And this is a legislator saying this, and so like when he says that people are going to assume he means it. And the way this worked with racial covenants is, theoretically, you could take someone to court if they violated the covenant, and they would lose the house, the house would revert back to the original person who put the covenant in. So the potential penalty was quite high for LEE HAWKINS: Oh, gosh. MICHAEL COREY: And I think, like, in practice, it's not like this is happening all the time. The way covenants work is that, like, no one's gonna mess with that because the consequence is so high. LEE HAWKINS: Is there any record of anybody ever breaking a covenant. MICHAEL COREY: Yeah, there are, like, there are legal cases where people either tried like, and people try a number of different strategies, like as Penny mentioned some of the early ones, they have this, like, laundry list of 19th century racial terms. And so it'll say, like, no Mongolian people, for example, like using this, like, racial science term. And so someone who is Filipino might come in and say, like, I'm not Mongolian, I'm Filipino. So, this professionalizing real estate industry keeps refining the covenants to be more, to stand up in court better. But I think for so many people, it's it's not worth the risk to break the covenant both white and like. For the white person, the stakes are low, right? Your neighbors might not like you. For people of color who are trying to break this color line, the stakes are the highest possible like like, because the flip side of a covenant is always violence. So I’m now clear on how these wealthy and powerful figures in my home state came up with a system to keep anybody who was not white locked out of the housing market. I’m still not clear on how these ideas spread around the country. MICHAEL COREY: these conferences that these real estate leaders, like the like the Thorpe brothers are going to like, this is the, this is the moment when these national Realty boards are being formed. And so all of these people are in these rooms saying, Hey, we've got this innovative technology. It's a racial covenant. And this private practice spreads rapidly after places that are in early. There's some places in the East Coast that are trying this this early too. This becomes the standard, and in fact, it gets written into the National Board of Realty ethics code for years because they're prominent people, they're also, like, going to be some of your elected officials there. And when you get to the era of the New Deal, like these are the people who are on the boards that are like, setting federal policy, and a lot of this stuff gets codified into federal legislation. So what starts as a private practice becomes the official policy of the US government when you get to the creation of the Federal Housing Administration that adopts essentially this, this concept that you should not give preferential treatment on loans to to integrate to neighborhoods that are going to be in harmonious and that same logic gets supercharged, because if we know something about this era, this is the FHA and then, and then the GI bill at the end of World War Two are a huge sea change in the way that housing gets financed and the way that homeownership sort of works. I learned so much from my conversations with Penny and Michael. We covered a lot of ground and at times I found myself overwhelmed by the weight of what I was hearing. What exactly does this mean today? What about the families who didn’t secure real estate through night dealings? The families who didn’t slip through the cracks of codified racial discrimination? How can we address these disparities now? In the final part of our series, we’ll hear from some of the people who benefitted, including relatives of Samuel Thorpe who have become new leaders in an old fight to make home ownership a reality for millions of Americans. MARGARET THORPE-RICHARDS: This could be the conversation. I feel like it's time to say something from my perspective. I have a platform, I have a voice, and I think it needs to be said and discussed and talked about, OUTRO MUSIC THEME/CREDITS You’ve been listening to Unlocking the Gates: How the North led Housing Discrimination in America. A special series by APM Studios AND Marketplace APM with research support from the Alicia Patterson Foundation and Mapping Prejudice. Hosted and created by me, Lee Hawkins. Produced by Marcel Malekebu and Senior Producer, Meredith Garretson-Morbey. Our Sound Engineer is Gary O’Keefe. Kelly Silvera is Executive Producer.

Integration Generation

Host Lee Hawkins investigates how a secret nighttime business deal unlocked the gates of a Minnesota suburb for dozens of Black families seeking better housing, schools, and safer neighborhoods. His own family included. TRANSCRIPT Intro LEE HAWKINS: This is the house that I grew up in and you know we're standing here on a sidewalk looking over the house but back when I lived here there was no sidewalk, and the house was white everything was white on white. And I mean white, you know, white in the greenest grass. My parents moved my two sisters and me in 1975, when I was just four years old. Maplewood, a suburb of 25,000 people at the time, was more than 90% white. As I rode my bike through the woods and trails. I had questions: How and why did these Black families manage to settle here, surrounded by restrictions designed to keep them out? The answer, began with the couple who lived in the big house behind ours… James and Frances Hughes. You’re listening to Unlocking The Gates, Episode 1. My name is Lee Hawkins. I’m a journalist and the author of the book I AM NOBODY’S SLAVE: How Uncovering My Family’s History Set Me Free. I investigated 400 years of my Black family’s history — how enslavement and Jim Crow apartheid in my father’s home state of Alabama, the Great Migration to St. Paul, and our later move to the suburbs shaped us. My producer Kelly and I returned to my childhood neighborhood. When we pulled up to my old house—a colonial-style rambler—we met a middle-aged Black woman. She was visiting her mother who lived in the brick home once owned by our neighbors, Mr. and Mrs. Hutton. LEE HAWKINS: How you doing? It hasn't changed that much. People keep it up pretty well, huh? It feels good to be back because it’s been more than 30 years since my parents sold this house and moved. Living here wasn’t easy. We had to navigate both the opportunities this neighborhood offered and the ways it tried to make us feel we didn’t fully belong. My family moved to Maplewood nearly 30 years after the first Black families arrived. And while we had the N-word and mild incidents for those first families, nearly every step forward was met with resistance. Yet they stayed and thrived. And because of them, so did we. LEE HAWKINS: You know, all up and down this street, there were Black families. Most of them — Mr. Riser, Mr. Davis, Mr. White—all of us can trace our property back to Mr. Hughes at the transaction that Mr. Hughes did. I was friends with all of their kids—or their grandkids. And, at the time, I didn’t realize that we, were leading and living, in real-time, one of the biggest paradigm shifts in the American economy and culture. We are the post-civil rights generation—what I call The Integration Generation. Mark Haynes was like a big brother to me, a friend who was Five or six years older. When he was a teenager, he took some bass guitar lessons from my dad and even ended up later playing bass for Janet Jackson when she was produced by Minnesota’s own Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis. Since his family moved to Maplewood several years before mine, I called him to see what he remembered. MARK HAYNES: "It's a pretty tight-knit group of people," Mark explained how the community came together and socialized, often – MARK HAYNES: "they—every week, I think—they would meet, actually. I was young—maybe five or six. LEE HAWKINS: And what do you remember about it? I asked. What kind of feeling did it give you? MARK HAYNES: It was like family, you know, all of them are like, uh, aunts and uncles to me, cousins. It just felt like they were having a lot of fun. I think there was an investment club too." Herman Lewis was another neighbor, some years older than Mark—an older teenager when I was a kid. But I remember him and his brother, Richard. We all played basketball, and during the off-season, we’d play with my dad and his friends at John Glenn, where I’d eventually attend middle school. Herman talked to me about what it meant to him. HERMAN LEWIS: We had friends of ours and our cousins would come all the way from Saint Paul just to play basketball on a Friday night. It was a way to keep kids off the street, and your dad was very instrumental trying to make sure kids stayed off the street. And on a Friday night, you get in there at five, six o'clock, and you play till 9, 10 o'clock, four hours of basketball. On any kid, all you're going to do is go home, eat whatever was left to eat. And if there's nothing left to eat, you pour yourself a bowl of cereal and you watch TV for about 15 to 25-30, minutes, and you're sleeping there, right in front of the TV, right? LEE HAWKINS: But that was a community within the community, HERMAN LEWIS: Definitely a community within the community. It's so surprising to go from one side of the city to the next, and then all of a sudden there's this abundance of black folks in a predominantly white area. Joe Richburg, another family friend, said he experienced our community within a community as well. LEE HAWKINS: You told me that when you were working for Pillsbury, you worked, you reported to Herman Cain, right? We're already working there, right? Herman Cain, who was once the Republican front runner for President of the United States. He was from who, who was from the south, but lived in Minnesota, right? Because he had been recruited here. I know he was at Pillsbury, and he was at godfathers pizza, mm hmm, before. And he actually sang for a time with the sounds of blackness, which a lot of people would realize, which is a famous group here, known all over the world. But what was interesting is you said that Herman Cain was your boss, yeah, when he came to Minnesota, he asked you a question, yeah. What was that question? Joe Richburg: Well, he asked me again, from the south, he asked me, Joe, where can I live? And I didn't really understand the significance of that question, but clearly he had a sense of belonging in that black people had to be in certain geographic, geographies in the south, and I didn't have that. I didn't realize that was where he was coming from. Before Maplewood, my family lived in St. Paul’s Rondo neighborhood—a thriving Black community filled with Black-owned businesses and cultural icons like photojournalist Gordon Parks, playwright August Wilson, and journalist Carl T. Rowan. Like so many other Black communities across the country, Rondo was destroyed to make way for a highway. it was a forced removal. Out of that devastation came Black flight. Unlike white flight, which was driven by fear of integration, Black flight was about seeking better opportunities: better funded schools and neighborhoods, and a chance at higher property values. Everything I’ve learned about James and Frances Hughes comes from newspaper reports and interviews with members of their family. Mr. Hughes, a chemist and printer at Brown and Bigelow, and Frances, a librarian at Gillette Hospital, decided it was time to leave St. Paul. They doubled down on their intentions when they heard a prominent real estate broker associate Blacks with “the ghetto.” According to Frances Hughes, he told the group; FRANCES HUGHES (ACTOR): “You’re living in the ghetto, and you will stay there.” She adds: FRANCES HUGHES (ACTOR): “I’ve been mad ever since. It was such a bigoted thing to say. We weren’t about to stand for that—and in the end, we didn’t.” The Hughes began searching for land but quickly realized just how difficult it could be. Most white residents in the Gladstone area, just outside St. Paul, had informal agreements not to sell to Black families. Still, James and Frances kept pushing. They found a white farmer, willing to sell them 10 acres of land for $8,000. And according to an interview with Frances, that purchase wasn’t just a milestone for the Hughes family—it set the stage for something remarkable. In 1957, James Hughes began advertising the plots in the Twin Cities Black newspapers and gradually started selling lots from the land to other Black families. The Hughes’s never refused to sell to whites—but according to an interview with Frances, economic justice was their goal. FRANCES HUGHES (ACTOR): “Housing for Blacks was extremely limited after the freeway went through and took so many homes. We wanted to sell to Blacks only because they had so few opportunities.” By the 1960s, the neighborhood had grown into a thriving Black suburban community. The residents here were deeply involved in civic life. They attended city council meetings, started Maplewood’s first human rights commission, and formed a neighborhood club to support one another. And over time, the area became known for its beautiful homes and meticulously kept lawns, earning both admiration and ridicule—with some calling it “The Golden Ghetto.” Frances said: FRANCES HUGHES (ACTOR): “It was lovely. It was a showplace. Even people who resented our being there in the beginning came over to show off this beautiful area in Maplewood.” And as I pieced the story together, I realized it would be meaningful to connect with some of the elders who would remember those early days ANN-MARIE ROGERS: In the 50s, Mr. Hughes decided he was going to let go of the farming. And it coincided with the with 94 going through the RONDO community and displacing, right, you know, those people. So, at that time, I imagine Mr. Hughes had the surveyors come out and, you know, divided up into, you know, individual living blocks. That is Mrs. Ann-Marie Rogers, the mother of Uzziel and Thomas Rogers, who I spent a lot of time with as a kid. I shared what I’d uncovered in the archives, hoping she could help bring those early experiences to life. ANN-MARIE ROGERS: So, everyone played in our yard, the front yard, the yard light that was where they played softball, baseball, because the yard light was the home plate, and the backyard across the back was where they played football. Throughout this project, we found similar stories of strength, including one from Jeson Johnson, a childhood friend with another Minnesota musical connection. His aunt, Cynthia Johnson, was the lead singer of Lipps Inc., whose hit song “Funkytown” became a defining anthem of its time when many of us were just kids. We were proud of her, but I now know the bigger star was his grandmother. JESON JOHNSON: She was actually one of the first black chemists at 3M. So what she told me is that they had told her that, well, you have to have so much money down by tomorrow for you to get this house. It was really, really fast that she had to have the money. But my grandmother was she was really smart, and her father was really smart, so he had her have savings bonds. So what she told him was, if you have it in writing, then I'll do my best to come up with the money. I don't know if I'll be able to. She was able to show up that day with all her savings bonds and everything, and have the money to get it. And they were so mad, yes, that when she had got the house, they were so mad that, but they nothing that they could do legally because she had it on paper, right, right? And then that kind of started out in generation out there. It was the NAACP that kind of helped further that, just because she was chemist, they got her in the 3M, and all their programs started there. Decades later, as my friends and I played, I had no concept of any of the struggles, sacrifices and steps forward made by the pioneers who came before us. I checked in with my friend, Marcel Duke. LEE HAWKINS: did they tell you that mister Hughes was the guy that started, that started it? MARCEL DUKE: It probably never was conveyed that way, right to us kids, right? I'm sure back then, it was looked as an opportunity, yes, to get out of the city. Mm, hmm, and and where people that look like us live. And obviously that's the backstory of Mister Hughes, yeah, ultimately, we went out there because he made it known in the city, inner city, that we could move out there and be a community out there. Marcel is about four years older, I figured he may have clearer memories of Mr. Hughes than I do. MARCEL DUKE: I used to cut mister Hughes grass. I was like, like the little hustler in the neighborhood. I wanted to cut because I wanted money to go to spend on candy. Mr. Hughes’ significance transcends the extra cash he put in the pockets of neighborhood kids. His granddaughter, Carolyn Hughes-Smith, told us more his multigenerational vision for Black American wealth building. But before he became a historical figure, he was just...grandpa. CAROLYN HUGHES-SMITH: the things that I really remember about him. He could whistle like I not whistle, but he could sing like a bird, you know, always just chirping. That's how we know he was around. He was more of a, like a farmer. He didn’t talk much with his grandchildren about how he and Frances had unlocked the gates for Blacks. But she was aware of some of the difficulty he faced in completing that transaction that forever changed Maplewood. HUGHES-SMITH: I just heard that they did not, you know, want to sell to the blacks. And they, you know, it was not a place for the blacks to be living. And so, what I heard later, of course, was that my grandpa was able to find someone that actually sold the land to him out there and it, you know, and that's where it all started, really That someone was a white man named Frank Taurek. He and his wife, Marie, owned the farm that Mr. Hughes and Frances had set their sights on. But the purchase was anything but straightforward. They had to make the deal through “night dealing.” Frances explains in a 1970s interview. FRANCES HUGHES (ACTOR): "It was just after the war. There was a tremendous shortage of housing, and a great deal of new development was going on to try to fix that. But, my dear, Negroes couldn't even buy a lot in these developments. They didn't need deed restrictions to turn us away. They just refused to sell." She describes the weekend visit she and her husband made to put in an offer on the land. By Monday morning, a St. Paul real estate company had stepped in, offering the Taurek’s $1,000 more to keep Blacks out. FRANCES HUGHES (ACTOR): "But he was a man of his word, which gives you faith in human nature. The average white person has no idea of how precarious life in these United States is for anybody Black at any level. So often it was a matter of happenstance that we got any land here. The farmer could have very easily accepted the $1,000 and told us no, and there would have been nothing we could have done." What led Frank Taurek to defy norms and his neighbors, to sell the land to a Black family? DAVIDA TAUREK: I'm already moved to tears again, just hearing about it, [but and] hearing you talk about the impact of my, you know, my lineage there. It seems so powerful. This perspective comes from his great-granddaughter, Davida Taurek, a California-based psychotherapist. When I tracked her down, she was astonished to hear the long-buried story of how her white great grandparents sold their land to a Black family, unwittingly setting into motion a cascade of economic opportunities for generations to come. DAVIDA TAUREK: When I received your email, it was quite shocking and kind of like my reality did a little kind of sense of, wait, what? Like that somehow I, I could be in this weird way part of this amazing story of making a difference. You know, like you said, that there's generational wealth that's now passed down that just didn't really exist. I’ve seen plenty of data about what happens to property values in predominantly white neighborhoods when a Black family moves in. The perception of a negative impact has fueled housing discrimination in this country for decades, you may have heard the phrase: “There goes the neighborhood.” It’s meant to be a sneer—a condemnation of how one Black family might “open the door” for others to follow. In this case, that’s exactly what the Taurek’s facilitated. As Carolyn Hughes- Smith sees it, the power of that ripple effect had a direct impact on her life, both as a youngster, but later as well. CAROLYN HUGHES-SMITH: We were just fortunate that my grandfather gave us that land. Otherwise, I don't, I don't know if we would have ever been able to move out there Her parents faced some tough times – CAROLYN HUGHES-SMITH: making house payments, keeping food in the house, and that type. We were low income then, and my dad struggled, and eventually went back to school, became an electrician. And we, you know, were a little better off, but that happened after we moved out to Maplewood, but we were struggling. But they persevered and made it through – CAROLYN HUGHES-SMITH: after I grow got older and teen and that, I mean, I look back and say, Wow, my grandfather did all of this out here On the Taurek side of the transaction, the wow factor is even more striking. As I dug deeper into his story, it wasn’t clear that he Frank Taurek was driven by any commitment to civil rights. Davida never met her great grandfather but explains what she knows about him. DAVIDA TAUREK: What I had heard about him was through my aunt that, that they were, you know, pretty sweet, but didn't speak English very well so there wasn't much communication but when they were younger being farmers his son my grandfather Richard ran away I think when he was like 14 years old. his dad was not very a good dad you know on a number of levels. There's a little bit of an interesting thing of like where Frank's dedication to his own integrity or what that kind of path was for him to stay true to this deal and make it happen versus what it meant to be a dad and be present and kind to his boy. Carolyn Hughes-Smith still reflects on the courage of her family—for the ripple effect it had on generational progress. CAROLYN HUGHES-SMITH: Would the struggle be the same? Probably not. But what makes me like I said, What makes me happy is our family was a big part of opening up places to live in the white community. LEE HAWKINS: Next time on Unlocking The Gates CAROLYN HUGHES-SMITH: The one thing that I really, really remember, and it stays in my head, is cross burning. It was a cross burning. And I don't remember exactly was it on my grandfather's property? OUTRO THEME MUSIC/CREDITS. You’ve been listening to Unlocking the Gates: How the North led Housing Discrimination in America. A special series by APM Studios AND Marketplace APM with research support from the Alicia Patterson Foundation and Mapping Prejudice. Hosted and created by me, Lee Hawkins. Produced by Marcel Malekebu and Senior Producer, Meredith Garretson-Morbey. Our Sound Engineer is Gary O’Keefe. Kelly Silvera is Executive Producer.

Bonus Episode: She Has A Name

We have a special episode for you today. We’re sharing an episode of the podcast She Has A Name. Set against the backdrop of the drug epidemic in 1980s Detroit, She Has A Name blends elements of investigative journalism, memoir, and speculative fiction to tell the story of Anita, a sister that Tonya learned about more than a decade after she went missing. It’s a story of loss and redemption, mending broken family ties, and facing the trauma experienced by countless individuals who've lost loved ones to violence. In this first episode, Tonya begins her quest to unravel how a sister she never knew about could end up as a Jane Doe. Here is Episode 1. If you’d like to hear more, you can find She Has A Name wherever you get your podcasts.

EP 10: Epilogue

In the final episode of What Happened In Alabama, Lee considers the man his father became, despite the obstacles in his way. Later, Lee goes back to Alabama and reflects with his cousins on how far they’ve come as a family. Now that we know what happened, Lee pieces together what it all means and looks forward to the future. ---------------------------------------- Over the last nine episodes, you’ve listened to me outline the impact of Jim Crow apartheid on my family, my ancestors and me. I’ve shared what I’ve learned through conversations with experts, creating connections to how the effects of Jim Crow manifested in my own family. In the process of this work I lost my father. But without him, this work couldn’t have been accomplished. My name is Lee Hawkins and this is What Happened In Alabama: The Epilogue Rev. James Thomas: You may be seated. We come with humble hearts. We come, dear Jesus, with sorrow in our hearts. But dear Jesus, we know that whatever you do,dear God,it is for your will and purpose. And it is always good. We buried my father on March 9, 2019. His funeral was held at the church I grew up in. Mount Olivet Baptist Church in St. Paul Minnesota. Rev. James Thomas: Dear God, I pray that you would be with this family. Like you have been with so many that have lost loved ones and even one day we all know we are going to sleep one day.Thank you for preparing a better place for us. Mount Olivet’s pastor, Rev. James Thomas, knew my parents well, especially since my father was part of the music ministry there for 30 years. It was a snowy day, but people came from all over Minnesota and from as far away as Prague to pay their last respects. I looked at the packed parking lot and all the cars lined up and down the street, and I felt a sense of gratitude in knowing that my dad had played such a strong role in so many people’s lives, not just the lives of his own children and family. Rev. James Thomas: Brother Leroy is probably playing the guitar over there. We can hear him with that squeak voice “yeeeee.” Jalen Morrison: We could talk about Prince, we could talk about gospel music. He was even up on the hip hop music, too, which kind of shook me up. But I was like, okay, Grandpa [laughter] Naima Ferrar Bolden: He really just had me seeing far beyond where I could see. He had me seeing far past my circumstances. He really changed my perspective, and that was just life altering for me ever since I was a little girl. Herman Jones: He just had the heavy, heavy accent. He still had that booooy. But you know,he was always smiling, always happy all the time. You know, just full of life. As I sat and listened to all the speeches that came before my eulogy of my dad, I couldn’t help but recognize both the beauty of their words and the extent to which my father had gone to shield so many of the people he loved from the hardest parts of his life—especially Alabama. It was as if he didn’t want to burden them, or, for most of our lives, his children, with that complexity. Most people remembered and honored him as that big, smiling, gregarious man with the smooth, first tenor voice, who lit up any space he was in and lit up when his wife, children, grandchildren, family, or friends walked into a room. He loved deeply; and people loved him deeply in return. And though he was victimized under Jim Crow, he was never a victim. In fact, after he sat for those four years of interviews with me for this show, opening up the opportunity for so many secrets to be revealed, he emerged as even more of a victor. In our last conversation, he told me he wasn’t feeling well and that he had been to the doctor three times that week, but was never tested for anything. And Dad, after that third visit, he just accepted it. I do wonder if there was ever a time in those moments that he had a flashback to his mother being sent home in a similar way - 58 years prior - but from a segregated Jim Crow Alabama hospital. I don’t know. I’ll never know. Tony Ware: Yeah. Mine. You know, I would always ask my mom, you know, about Alabama. You know, she was one of the five that came up here. That’s my cousin Tony Ware. His mom was my Aunt Betty. The “five” that he’s talking about were my Dad’s siblings who migrated to Minnesota from Alabama - my aunts Helen, Toopie, Dorothy, Betty, and my Dad. Tony Ware: They kind of hung around together and they would always have sit downs where they would talk. Get a moon pie, a soda. Hmm. Some sardines. Lee Hawkins: Cigarettes. Tony Ware: Cigarettes, sardines. And they would start talking. And some white bread. And they would sit there and talk and we would hear some of it. I sat in my mom's lap, and you know, they're talking about this, and it's like they just went into a different world. When I was a kid in Minnesota, I loved when my dad’s sisters and their kids would come over. Us cousins would play hide-and-seek and listen to our music while our parents sat around the dining room table, talking and laughing, and listening to their own music. Our soundtrack was always great – Prince, Michael Jackson, New Edition, Cameo – but theirs was, too, with Curtis Mayfield, Aretha Franklin, Jerry Butler, Johnny Taylor, and Bobby Womack. The food was even better. They’d talk over one another, smoke clouding the air under the chandelier, and my allergy-sensitive nose could detect that smell from three rooms away. Sometimes, I’d sneak a quick sip from an unattended can of beer in the kitchen. Despite the bitter taste, getting away with it always gave me a thrill. But then, someone would mention the word “Alabama,” and that festive energy would suddenly vanish. Tony Ware: But I heard Alabama. I heard this. I heard names that I never, you know, heard, you know, because all I knew was my aunt Dorothy, Lee Roy, you know, all I knew was. But then I heard certain names, uncles such and such. And I'm like, Who? Who, what, what? To us as kids, "Alabama" was more than a place—it was a provocative word that brought a suffocating heaviness to our lives. My cousin Gina remembers, even as a child, that mysterious word and the weariness it triggered in her mother. It left her feeling utterly helpless. Gina Hunter: And I would just sit there and listen to them talk about home and all the things that bothered them. Oh, my God. And yeah, it would hurt my feelings because I would see my mom just break out and cry for nothing. They would be talking and a song would be playing and Betty would just kind of get, she'd well up. Lee Hawkins: Yeah. Gina Hunter: And I'm like, Why are they so sad? Why are they so depressed? They they're together. They've got their kids. We're visiting, we're having fun. But it wasn't fun for them. That veil of secrecy our parents kept around Alabama, prevented us from seeing it as anything other than ground zero for, in our family, dreadful despair. Even when they talked about the happy memories— the church revivals that they called “big meeting,” and picking fresh strawberries right off the vine – it seemed like a thread of fear just wove through almost every story. Tony Ware:I knew something was going on more than what I knew here, you know, at a young age. So. I was always interested in finding out. But through my mom, you know, she she would talk about how nice it was down there, how beautiful it was down there. But she never wanted to go back there. And as Gina remembers– and I agreed– it colored every facet of how they raised us. As she spoke, I just sat there, marveling at the fact that she could have replaced her mom’s name with my dad’s name, or any one of those siblings, and her observations would still be spot on. Gina Hunter:My mom was and Aunt Helen, they were super, super close. And there was always just a deep seeded paranoia of people in general, just like everything. And I would think, why are these people why are they so scared and nervous and afraid of life and people and experiencing things? It seemed like it led them to live a super sheltered life. The central question of this podcast is, "What happened in Alabama?" What happened was Jim Crow apartheid—a crime against humanity committed by the American government against five generations of Black families like mine. This apartheid lasted for nearly hundred years, officially ending in 1964, and created generations of people who perished and millions who survived. I refer to these individuals as Jim Crow apartheid survivors. However, America has yet to acknowledge that Jim Crow was apartheid, that it was a crime against humanity, and that the millions of people who lived through it should be formally recognized as survivors. In the prologue, I explained that so-called Jim Crow segregation was not merely about separate water fountains and back-of-the-bus seating. Through the accounts of family trauma I’ve shared, we now understand it was a caste system of domestic terrorism and apartheid, enforced by a government that imposed discrimination in every aspect of life through laws and practices designed to maintain white supremacy. The myth of "separate but equal" masked a reality far more sinister and pervasive than what most of us were taught in school. We often think of white supremacy as fringe hate groups, but we’ve overlooked its traditional and far more damaging form—a government-imposed system that oppressed Black people for a century after emancipation. This isn't a distant academic concept or an opinion or a loaded political statement; it’s a fact. This is recent American history, and it deeply impacted our families, controlling every aspect of our lives physically, mentally, and emotionally for five generations after slavery. Since 1837, every generation of my family in America has had a member murdered, often with no consequences for the white perpetrator. The fear, caution, and grief were passed down by those who stood around the caskets, including my father. The daily indignities only compounded this grief, leading to accelerated aging and chronic stress that I believe ultimately killed my father. Yes, Jim Crow apartheid killed my father. Still, I’m encouraged because I have the platform to tell this aspect of the story. Sharing this story has been extremely difficult, but I’ve been lifted not just by my faith and ancestors but also by my family, their support, optimism, and determination. With this new information, we live with the awareness of the effects of slavery and Jim Crow, striving to break their negative cycles and be empowered by the accomplishments of our families who found ways to thrive despite the oppression caused by those crimes. Telling this story has fortified my resolve, reminding me that our past is not just a story of struggle, but of relentless triumph and dignity. For generations, we have managed to thrive together as a family. By infusing even more consciousness and evolution into our families with each generation, we can continue to thrive. That’s why I’m grateful for my cousins, including my first cousin, David Stanley, the son of my dad’s sister, Aunt Weenie, who articulated this sentiment powerfully during an interview with my cousins, my father's sisters' children. David Stanley: I think it’s a new form of freedom, OK. And even though they faced the backwardness of Jim Crow and all those things that our ancestors went through, they still had their dreams and dignity. And no matter what happened, it's not about the environment around you, it’s the environment inside of you. ‘You're not going to stop us. We're going to continue to grow. So by doing that, they said, ‘Okay, you know what? We are going to plant the seed, our offspring, okay?’ You can do this in our generation during this time, but guess what? There's another generation coming up.’ And that triggers all the way to us today. And then you got your nieces and your nephew, and then you got grandkids, et cetera. Lee: Yeah. And your kids have all master's degree and PhDs. And then your wife is a superintendent of a school district. David: That's right. Yep. So they left their seed, they left their vision. And my point is that I believe that they are all up in heaven smiling down on us and really proud of us. David: I have to go and take that trip to Alabama and bring my children with me and my grandkids with me, because it's vital. Because you put that out there, I really appreciate that. That’s something that’s definitely going to be done ,and I think that’s something that we all need to do, to rekindle and reconnect and do those things. The past can’t hurt you, but my point is that by being in the present right now, now we can solidify our future, you know what unapologetically. And do the things they were always yearning to do, in their lives. And they couldn’t do them. But they can do them through us. Lee Hawkins: A lot of it is facing your parents' fears,that’s what it id. for them as well. My dad really loved Alabama. He did. And my dad would talk about that in a very nostalgic way, but also the fear was still there. And so when I started going to Alabama, I was going for him as well. Not to mention, I have had a couple of people in the family say, ‘Oh be careful down there.’ And Aunt Toopie even said, ‘You went in that field? You went to that cemetery?’ That fear was on me when I first went to Alabama. The last trip that we went to, I did it with family. Walking through the cemeteries and the landscapes of Alabama alongside my family who live there transformed my mission, helping me to finally lay my father’s fear to rest. Lee Hawkins: Mary Ruth’s Southern Food for Southern People Made with Love. I love that. That slogan. Marvin Smith: Welcome to Mary Ruth's. Thank you for coming. Lee Hawkins: You got some grits on the griddle huh. Marvin Smith: Oh I got it all. Got me some grits, cheese grits, patty sausage, salmon croquettes, link sausage, bacon. Whatever you ask for we'll cook it. Pancakes, whatever. Hey, we aint Burger King but you can sure get it your way though. Group: [Laughter] There’s so much energy in the cafe. I feel the family. My family. We spend a couple hours eating together. Mapping family connections. People come into the cafe, some grab their food and take a seat, some join us. A woman walks in the door and she recognizes me…. not because she knows who I am, but because of my resemblance to her husband, he’s also a Pugh. Erica Page: Y'all got a line that will not just go away. It's strong genes. You'll have strong and strong. Yes, cause I have a daughter and a grandson. Oh, God. Looks just like him Her name is Erica Page. Lee Hawkins: You know, Uncle Ike Pugh? Erica Page: We went to the house several times. At one point, someone pulls out a family reunion book. It’s a laminated, spiral bound scrapbook. Someone put a lot of work into making it. We’re flipping through the pages together…. Lee Hawkins: My grandma was Opie Pugh. Erica Page: I know the name. Lee Hawkins: She was. Well, she was Ike's sister. Erica Page: I know. I know the name.I means she's in the book. We find pictures of our Pugh ancestors, Uncle Ike and my dad’s mom, Grandma Opie. I’ve seen these photos before through my research into the family tree. But suddenly, Alabama feels different from the times I visited before for research. I am not surprised that the shift in my relationship with Alabama was guided by my family members who chose to stay rather than migrate north. They stayed and evolved Alabama to the point where both Montgomery and Birmingham now have African American mayors. They, and the millions of Black people who stayed, led a movement that benefits all Americans today. In discussing the hardships my family endured there, it is important to recognize that the progress of our people and our nation is largely attributable to the activism of the courageous Black Americans who stayed and fought. These same Black Americans welcomed me back to Alabama with open arms and support, encouraging me to move forward with this project. They reminded me not to be resentful or afraid to come home, to give Alabama a chance, and to offer it the same benefit of the doubt and acknowledgment of complexity that I give my country. Understanding that it was our families, the Black descendants of American slavery, who led the movement that resulted in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, ending Jim Crow apartheid and bringing America closer to liberty and justice for all, reinforces the reality that, despite significant trauma, we have remained a solutions-oriented people, some of the most effective activists this nation has ever known. Their legacy and courage have shaped Alabama and America and their spirit of irrepressibility continues to inspire me. In my forthcoming book, "I Am Nobody’s Slave: How Uncovering My Family History Set Me Free," published by HarperCollins, I will strive to capture not just the stories of trauma but how we can continue to conquer it as a family, a Black American community, and a nation. Inspired by the spirit of my ancestors and my father, who transcended the limitations Alabama tried to impose on him, I will continue my journalism on several issues discussed in this series. These include exposing and addressing the long-term effects of corporal punishment in homes and schools, the impact of childhood trauma on the health and well-being of children, encouraging school districts to implement policies of mandatory consequences for hate speech and harassment, and highlighting economic and health inequities along racial lines. I will also focus on the plight and power of Jim Crow apartheid survivors as they strive to quell the ripple effect of historical atrocities on their families. The question now is, what can we all do as a nation to recognize Jim Crow as a crime against humanity and to support the millions of Americans over 60 who lived in the South during this unfortunate period? How can we make our homes, schools, and society safer for the generations of children and grandchildren coming behind them? Together, we can acknowledge our past, honor the strength of those who came before us, and build a future filled with hope, determination, and joy. Let us rise with the resilience of our ancestors and create a world where every child can dream freely and every family can thrive. Lee Roy: You've run the game and you know the Lord and you're doing your thing, man. And that's the best you can do as far as I'm concerned. You have to keep your heart and your head up. I don't know this thing about being proud. I know the Lord and I know the Lord loves me. So if I'm proud, man, please forgive me and if I shouldn't be, but it is a poor dog that don't wag his own tail, son, when you're trying to reach your goals, I'll put it like that, you know. Lee Jr.: Right on. Well, okay buddy, I'm going to hit it, but I'll be in touch, okay? Lee Roy: Yeah, keep going, man, I'm loving it. I'm loving what we're doing, Lee. Lee Jr.: Okay, love you, Dad. Lee Roy: Okay man. Love you. Bye. CREDITS

Choose your subscription

Limited Offer

Premium

20 hours of audiobooks

Podcasts only on Podimo

All free podcasts

Cancel anytime

2 months for 19 kr.

Then 99 kr. / month

Premium Plus

Unlimited audiobooks

Podcasts only on Podimo

All free podcasts

Cancel anytime

Start 7 days free trial

Then 129 kr. / month

2 months for 19 kr. Then 99 kr. / month. Cancel anytime.