The Mises Report

Podcast de Mises Institute

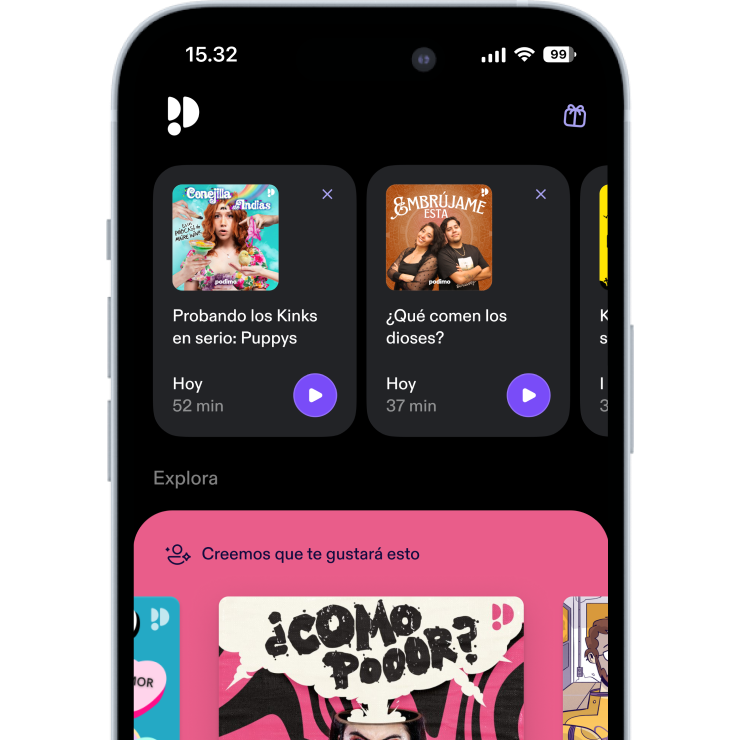

Empieza 7 días de prueba

$99.00 / mes después de la prueba.Cancela cuando quieras.

Más de 1 millón de oyentes

Podimo te va a encantar, y no estás solo/a

Rated 4.7 in the App Store

Acerca de The Mises Report

Recorded by the Mises Institute in the mid-1980s, The Mises Report provided commentary from leading non-interventionists, economists, and political scientists.

Todos los episodios

8 episodiosRecorded by the Mises Institute in the mid-1980s, The Mises Report provided radio commentary from leading non-interventionists, economists, and political scientists. In this program, we present another part of "Ten Great Economic Myths". This material was prepared by Murray N. Rothbard. The public memory is short. We forget that, from the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the mid-18th century until the beginning of World War II, prices generally went down, year after year. That's because continually increasing productivity and output of goods generated by free markets caused prices to fall. There was no depression, however, because costs fell along with selling prices. Usually, wage rates remained constant while the cost of living fell, so that "real" wages, or everyone's standard of living, rose steadily. Virtually the only time when prices rose over those two centuries were periods of war (War of 1812, Civil War, World War I), when the warring governments inflated the money supply so heavily to pay for the war as to more than offset continuing gains in productivity. We can see how free market capitalism, unburdened by governmental or central bank inflation, works if we look at what has happened in the last few years to the prices of computers. A computer used to have to be enormous, costing millions of dollars. Now, in a remarkable surge of productivity brought about by the microchip revolution, computers are falling in price even as I write. Computer firms are successful despite the falling prices because their costs have been falling, and productivity rising. In fact, these falling costs and prices have enabled them to tap a mass market characteristic of the dynamic growth of free market capitalism. "Deflation" has brought no disaster to this industry. The same is true of other high-growth industries, such as electronic calculators, plastics, TV sets, and VCRs. Deflation, far from bringing catastrophe, is the hallmark of sound and dynamic economic growth. For more episodes, visit Mises.org/MisesReport

Recorded by the Mises Institute in the mid-1980s, The Mises Report provided radio commentary from leading non-interventionists, economists, and political scientists. In this program, we present another part of "Ten Great Economic Myths". This material was prepared by Murray N. Rothbard. Every time someone calls for the government to abandon its inflationary policies, Establishment economists and politicians warn that the result can only be severe unemployment. We are trapped, therefore, into playing off inflation against high unemployment, and become persuaded that we must therefore accept some of both. This doctrine is the fallback position for Keynesians. Originally, the Keynesians promised us that by manipulating and fine-tuning deficits and government spending, they could and would bring us permanent prosperity and full employment without inflation. Then, when inflation became chronic and ever-greater, they changed their tune to warn of the alleged tradeoff, so as to weaken any possible pressure upon the government to stop its inflationary creation of new money. The tradeoff doctrine is based on the alleged "Phillips curve," a curve invented many years ago by the British economist A. W. Phillips. Phillips correlated wage rate increases with unemployment, and claimed that the two move inversely: the higher the increases in wage rates, the lower the unemployment. On its face, this is a peculiar doctrine, since it flies in the face of logical, commonsense theory. Theory tells us that the higher the wage rates, the greater the unemployment, and vice versa. If everyone went to their employer tomorrow and insisted on double or triple the wage rate, many of us would be promptly out of a job. Yet this bizarre finding was accepted as gospel by the Keynesian economic establishment. By now, it should be clear that this statistical finding violates the facts as well as logical theory. For during the 1950s, inflation was only about one to two percent per year, and unemployment hovered around three or four percent, whereas nowadays unemployment ranges between eight and 11 percent, and inflation between five and 13 percent. In the last two or three decades, in short, both inflation and unemployment have increased sharply and severely. If anything, we have had a reverse Phillips curve. There has been anything but an inflation-unemployment tradeoff. But ideologues seldom give way to the facts, even as they continually claim to "test" their theories by facts. To save the concept, they have simply concluded that the Phillips curve still remains as an inflation-unemployment tradeoff, except that the curve has unaccountably "shifted" to a new set of alleged tradeoffs. On this sort of mind-set, of course, no one could ever refute any theory. In fact, inflation now, even if it reduces unemployment in the short-run by inducing prices to spurt ahead of wage rates (thereby reducing real wage rates), will only create more unemployment in the long run. Eventually, wage rates catch up with inflation, and inflation brings recession and unemployment inevitably in its wake. After more than two decades of inflation, we are all now living in that "long run." For more episodes, visit Mises.org/MisesReport

Recorded by the Mises Institute in the mid-1980s, The Mises Report provided radio commentary from leading non-interventionists, economists, and political scientists. In this program, we present another part of "Ten Great Economic Myths". This material was prepared by Murray N. Rothbard. The problem of forecasting interest rates illustrates the pitfalls of forecasting in general. People are contrary cusses whose behavior, thank goodness, cannot be forecast precisely in advance. Their values, ideas, expectations, and knowledge change all the time, and change in an unpredictable manner. What economist, for example, could have forecast (or did forecast) the Cabbage Patch Kid craze of the Christmas season of 1983? Every economic quantity, every price, purchase, or income figure is the embodiment of thousands, even millions, of unpredictable choices by individuals. Many studies, formal and informal, have been made of the record of forecasting by economists, and it has been consistently abysmal. Forecasters often complain that they can do well enough as long as current trends continue; what they have difficulty in doing is catching changes in trend. But of course there is no trick in extrapolating current trends into the near future. You don't need sophisticated computer models for that; you can do it better and far more cheaply by using a ruler. The real trick is precisely to forecast when and how trends will change, and forecasters have been notoriously bad at that. No economist forecast the depth of the 1981–82 depression, and none predicted the strength of the 1983 boom. The next time you are swayed by the jargon or seeming expertise of the economic forecaster, ask yourself this question: If he can really predict the future so well, why is he wasting his time putting out newsletters or doing consulting when he himself could be making trillions of dollars in the stock and commodity markets? For more episodes, visit Mises.org/MisesReport

Recorded by the Mises Institute in the mid-1980s, The Mises Report provided radio commentary from leading non-interventionists, economists, and political scientists. In this program, we present another part of "Ten Great Economic Myths". This material was prepared by Murray N. Rothbard. The financial press now knows enough economics to watch weekly money supply figures like hawks; but they inevitably interpret these figures in a chaotic fashion. If the money supply rises, this is interpreted as lowering interest rates and inflationary; it is also interpreted, often in the very same article, as raising interest rates. And vice versa. If the Fed tightens the growth of money, it is interpreted as both raising interest rates and lowering them. Sometimes it seems that all Fed actions, no matter how contradictory, must result in raising interest rates. Clearly something is very wrong here. The problem here is that, as in the case of price levels, there are several causal factors operating on interest rates and in different directions. If the Fed expands the money supply, it does so by generating more bank reserves and thereby expanding the supply of bank credit and bank deposits. The expansion of credit necessarily means an increased supply in the credit market and hence a lowering of the price of credit, or the rate of interest. On the other hand, if the Fed restricts the supply of credit and the growth of the money supply, this means that the supply in the credit market declines, and this should mean a rise in interest rates. And this is precisely what happens in the first decade or two of chronic inflation. Fed expansion lowers interest rates; Fed tightening raises them. But after this period, the public and the market begin to catch on to what is happening. They begin to realize that inflation is chronic because of the systemic expansion of the money supply. When they realize this fact of life, they will also realize that inflation wipes out the creditor for the benefit of the debtor. Thus, if someone grants a loan at 5% for one year, and there is 7% inflation for that year, the creditor loses, not gains. He loses 2%, since he gets paid back in dollars that are now worth 7% less in purchasing power. Correspondingly, the debtor gains by inflation. As creditors begin to catch on, they place an inflation premium on the interest rate, and debtors will be willing to pay. Hence, in the long-run anything which fuels the expectations of inflation will raise inflation premiums on interest rates; and anything which dampens those expectations will lower those premiums. Therefore, a Fed tightening will now tend to dampen inflationary expectations and lower interest rates; a Fed expansion will whip up those expectations again and raise them. There are two, opposite causal chains at work. And so Fed expansion or contraction can either raise or lower interest rates, depending on which causal chain is stronger. Which will be stronger? There is no way to know for sure. In the early decades of inflation, there is no inflation premium; in the later decades, such as we are now in, there is. The relative strength and reaction times depend on the subjective expectations of the public, and these cannot be forecast with certainty. And this is one reason why economic forecasts can never be made with certainty. For more episodes, visit Mises.org/MisesReport

Recorded by the Mises Institute in the mid-1980s, The Mises Report provided radio commentary from leading non-interventionists, economists, and political scientists. In this program, we present another part of "Ten Great Economic Myths". This material was prepared by Murray N. Rothbard. Those people who are properly worried about the deficit unfortunately offer an unacceptable solution: increasing taxes. Curing deficits by raising taxes is equivalent to curing someone's bronchitis by shooting him. The "cure" is far worse than the disease. For one reason, as many critics have pointed out, raising taxes simply gives the government more money, and so the politicians and bureaucrats are likely to react by raising expenditures still further. Parkinson said it all in his famous "Law": "Expenditures rise to meet income." If the government is willing to have, say, a 20 percent deficit, it will handle high revenues by raising spending still more to maintain the same proportion of deficit. But even apart from this shrewd judgment in political psychology, why should anyone believe that a tax is better than a higher price? It is true that inflation is a form of taxation, in which the government and other early receivers of new money are able to expropriate the members of the public whose income rises later in the process of inflation. But, at least' with inflation, people are still reaping some of the benefits of exchange. If bread rises to $10 a loaf, this is unfortunate, but at least you can still eat the bread. But if taxes go up, your money is expropriated for the benefit of politicians and bureaucrats, and you are left with no service or benefit. The only result is that the producers' money is confiscated for the benefit of a bureaucracy that adds insult to injury by using part of that confiscated money to push the public around. No, the only sound cure for deficits is a simple but virtually unmentioned one: cut the federal budget. How and where? Anywhere and everywhere. For more episodes, visit Mises.org/MisesReport

Rated 4.7 in the App Store

Empieza 7 días de prueba

$99.00 / mes después de la prueba.Cancela cuando quieras.

Podcasts exclusivos

Sin anuncios

Podcast gratuitos

Audiolibros

20 horas / mes