Singing Homer Podcast

Podcast de A P David

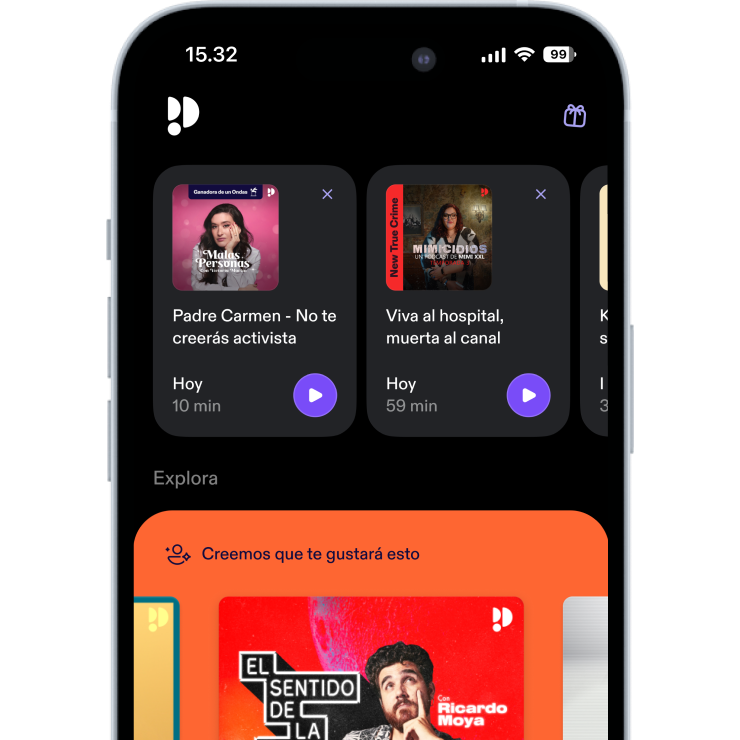

Disfruta 90 días gratis

9,99 € / mes después de la prueba.Cancela cuando quieras.

Más de 1 millón de oyentes

Podimo te va a encantar, y no sólo a ti

Valorado con 4,7 en la App Store

Acerca de Singing Homer Podcast

A performance of Homer's Odyssey in ancient Greek, with texts. homerist.substack.com

Todos los episodios

60 episodiosOdyssey 10.80-134 The episode of the Laestrygonians is a mix of old and new, familiar and unfamiliar. I suppose that in these episodes of Odysseus’ wanderings, which are relatively self-contained, one is still faced with the problem of sequencing: in the sense that whatever architectonic ideas the teller may have, from moment to moment there will be the concern with the segue, of maintaining interest and sustaining the narrative energy of what has come before. The story of the Aeolian Isle, which contains Aeolus’ musically violent rebuke of Odysseus, has managed the problem divertingly. But by any measure, the long and intensely involving episode of the Cyclops must still be considered a hard act to follow. By contrast, it seems to me the episode of the Lotus-Eaters might have been placed almost anywhere to good effect: by itself it distils the gist, of the human longing for physical satisfaction and psychic escape, countering the longing (and need) for home. After moving on from the Aeolian Isle and the desperate frustration of almost getting home—not for the first time (see 9.79)—we are immediately regaled with the spice of a traveller’s tale: For six days then we sailed, day and night the same, But on the seventh we arrived at the steep citadel of Lamus, Telepylus of Laestrygonia—where herdsman to herdsman Calls out, as he drives them in, but the other responds as he drives them out. There an unsleeping man could pick up two wages, The one for tending cattle, the other pasturing flocks of white sheep: For close by are the paths of the night and of the day. (10.80-86) One calls this a traveller’s tale in part because it is hard to make sense of it from the perspective of, say, geography. The paths of the night and day (νυκτός τε καὶ ἤματα … κέλευθοι) must mean the track of the sun’s daily motion. The points of sunset and sunrise on the horizon do come closer and closer together the further north or south you go before reaching the arctic circle or the antarctic one, at the respective midwinters and midsummers. One presumes midsummer is on Homer’s mind here, because the night then, in those regions, would be short, with the sun briefly dipping beneath the horizon and rising again only slightly to the east. Perhaps the ambitious herdsman could skip sleep and tend two herds of crepuscular grazers, one evening and one morning. Or so the foreigners imagine. People still imagine all kinds of things about the tropics, just from spending gated vacations there. Perhaps what Homer had heard about these regions was that the shortness of the midsummer night was a permanent condition, rather than a seasonal one. Whatever the case, Homer’s audience must have been from a region further towards the equator, where the nights were always long enough for a bout of sleep, and a single day’s wages had to do for a shepherd. Traveller’s tales score points with exotic twists to daily routines and schedules, not fine points of husbandry and geography. The prejudices induced by the premises of modern Homeric scholarship tend toward breaking apart Homer’s massive poem into smaller units: songs and episodes. Partly this instinct is natural from the premise of formulaic oral improvisation and the oral aural groupings reflected in ‘ring composition’. But it also takes its cue from depictions of performance inside the poems; we have witnessed several performances of Demodocus, for example, some by hearsay but one, the love story of Ares and Aphrodite, in full opera. These suggest after-dinner entertainments of, at most, several hundred lines, on quite a different scale from the many thousands of lines of each of the Iliad and the Odyssey. On the other hand, we have it from Athenian authorities including Plato, that a rule was instituted in Athens during the time of Hipparchus, son of the tyrant Peisistratus, that Homer’s lines needed to be performed in order: when one rhapsode finished—whether exhausted or at his preferred time—the next must take up the song exactly at the line where the first left off. One source attributes this law instead to Solon, so that performing Homer could be conceived as a sort of team relay. Both accounts suggest that Homer’s lines came to Athens as known and complete sets of things, of considerable size and a fixed order, like Wagner’s Ring or a multi-volume novel, which required a number of soloists in sequence to perform them coherently in sequence. In the modern concert hall, it was once the standard practice to excerpt movements from different pieces and composers, so as to ‘compose’ an evening of variety, taste, and harmony … More recent audiences of ‘classical’ music, like those of Peisistratean Athens in relation to Homer, have [instead] demanded whole compositions in their original sequence. Consider that such a demand begins in the audience, and bespeaks either an intimacy with the original whole as a whole, or, at the very least, the knowledge that such a whole exists. The Lotus-Eaters notwithstanding, there does seem to be an order to Odysseus’ episodes. Consider the mystery of his fleet’s eleven other ships. They occupy a most peculiar psychic dimension in the storyteller’s imagination. Twelve in number were the ships which escaped the Cicones and followed Odysseus to land at night, by accident—‘it was some god guided us’—at the goat-filled island opposite the Cyclopean shore. The next day nine goats went to each ship, but ten to Odysseus’; at home or encamped at Troy he might have been a king or chieftain, but in their escape from there Odysseus seems to receive the honour merely of a captain, a first among equals. Perhaps the political order of the world has changed somehow. How might this democratic flight on board ship affect the standing of his men when they arrive back home in quasi-feudal Ithaca? This is not a question we shall have to face, it turns out. But it remains the case that when he gets home, Odysseus will have to prove his worth in rags, including his worthiness to rule. On the second day at dawn, Odysseus makes an announcement with no explanation: only he and his ship’s crew will go to explore the land opposite, the land of the Cyclopes. Hence eleven ships miss entirely the adventure with the Cyclops, the giant, the terror, and the cannibalism; and so, it seems, they miss out on any experience gained or lessons learned. They witnessed nothing, not Odysseus’ three vaunts to Polyphemus, nor the hurled mountain tops, nor the terror of the water’s backward surge. In a very real sense, we in the audience are closer witnesses to those events than they will ever be. Hence the men of these eleven ships become a sort of void or null space in the story, and in our experience of it. The only thing evident to such non-participants may be that Odysseus’ leadership has been a failure. This conclusion would no doubt be reinforced after the harrowing round trip, blown back from the sight of Ithaca’s home fires to the distant Isle of Aeolus. Now, when they reach the inlet and cove of the Laestrygonians, it does not appear that Odysseus’s ship is in the lead any more at all. No, the eleven mystery ships traipse into the narrow inlet and blithely tie their ships in the calm waters within. But I alone kept my black ship outside, Where I was at the edge, having tied my cables off the cliff. And I stood at a lookout point, once I went up the rough and rocky way. From there neither the operations of cattle nor of men appeared, But we saw only smoke, rising from the ground. (95-99) Why do Odysseus and his crew not enter, but rather tie their ship outside? The man himself does not tell us. Is it that they alone have learnt the lessons of caution after nearly succumbing to the Cyclops? That could be simply true, but perhaps there is also a more sinister implication: is Odysseus no longer in charge of the fleet? Has he in fact been deposed? Odysseus hints at nothing of the kind, but the evidence is plain to see: where the other eleven ships had once been following his—‘The ships that followed me (μοι ἕποντο) were twelve in number’ (9.159)—now they’ve gone on ahead, seemingly unaware that their erstwhile captain is not with them. Could there even be hostility between him and them? No intent is apparent or hinted at, but it does so happen that it is the actions initiated by Odysseus and his ship’s crew which first alert the Laestrygonians to the presence of the rest of the fleet in the harbour, and which lead to the surreal scene of their slaughter. May one wonder if Odysseus feels, at the end of the day, that their fate had served them right? The whole episode seems a bit of a sendup. Odysseus sends off two unnamed men, with a third ‘as a herald,’ to follow the mountain road into town and see what they see. They run into a girl fetching water, a Rebecca at the well. The scene seems set for flirtation. Chance meetings at the water well decide history. These men must not remember when they last saw a friendly girl. She turns out to be the daughter of a Laestrygonian heavy, one Antiphates, ‘Against Speech’, who, true to his name, shall have no lines. She herself is nameless, unless her epithet is her name: Ἰφθίμη, a derivation from ϝίς suggesting ‘strong’, ‘valiant’, ‘sturdy’. It is most likely functioning as a title, whose literal meaning is not necessarily in the foreground; as when subjects say, for example, ‘Your Excellency’ or ‘Majesty’ or ‘Highness’. Yet I cannot resist translating ‘Beefy’. I reckon she was a pretty big girl. There was no danger of these lonely sailors having their way with that one. She takes the men home, they round the corner and it’s ‘Hello, Mum!’. Except she’s a giantess as tall as a mountain. They are aghast at her. Mum’s in charge around here, as she seems to be most places outside the land of the Cyclopes. The rest of Odysseus’ adventures seem to be exclusively in the face of threats to his life and masculinity from feminine forces. It’s a sorry shift for a man in arms, used to engaging on the battlefield where men know what the rules are about hitting below the belt. Mrs. Antiphates yells out for her husband, up to no good, as no doubt he usually was, hanging out in the marketplace; Antiphates dutifully rushes home and straight away eats one of Odysseus’ men. Not sure if it’s the herald who wears the red shirt. Now, when we meet the Cyclops, the original cannibal giant, there is terror in anticipation. Homer and Odysseus paint the scene with a novelist’s and a cinematographer’s touch: Polyphemus looms long in the presence before we meet him. ‘Let’s just grab some of this cheese and get out of this creepy place!’ We hear him before we see him: he throws down a huge weight of dry timber outside the cave while Odysseus and his men tremble inside. He then blocks the door with an immense, unshiftable stone. And when he finishes his milking chores and finally notices the little men, they are terrified at the sheer depth of his voice. The sense of ‘I’ve got a bad feeling about this’ builds exquisitely. When the Cyclops snatches up and eats Odysseus’ men, there is abrupt revulsion and gruesome shock. With Antiphates and his wife, however, and the friendly daughter, the scene is almost comical. The confrontation with the mountain-sized woman is both sudden and unanticipated, too unexpected to be shocking. The henpecked husband comes home and eats the strangers almost as a domestic duty. The effect is more surreal than revolting, macabre rather than gruesome and savage. And the tableau which follows only taps further into the surreal. The rest of the beefy Laestrygonians are roused to head to the harbour, where they proceed to go spear-fishing in a tidal pool, by throwing huge rocks like pebbles at the writhing creatures trapped within. The eleven ships provide themselves as fresh seafood for happy hour! These alien men are called ‘giants’, but I can’t help translating ‘gigantes’. This is a correct transliteration, but it is also what modern Greeks call the giant beans they cook so wonderfully. Says Odysseus: While they were destroying the men within the depths of the harbour, I drew my sharp sword from beside my thigh, (125-6) That last line recurs in the Iliad, ‘I drew my sharp sword from beside my thigh.’ Sometimes a sword is just a sword. Usually in the Iliad this line precedes the description of some exploit in battle, a use of the sword in combat. A version occurs when Achilles briefly contemplates drawing his sword to kill Agamemnon, right then and there during the public confrontation which begins that poem. If the depiction of Antiphates’ household is, in part, a self-parody of what Homer has achieved in his tale of the Cyclops, here we arrive at meta-parody, satire even, at the expense of the poet’s trade in the Iliad. A line designed to create expectation of some devastating act of war, is here allowed to poof into magician’s flowers. In the Odyssey, the lines continue: And I struck off the stern cables of the cobalt-prowed ship with it. (127) Odysseus’ ship is parked outside the inlet, out of sight of the mêlée within. He draws his sword to cut the cables and escape. ‘Run away! Run away!’ say Monty Python’s Knights of the Round Table. In gladness into the deep she escaped the overhanging cliffs— My own ship, that is; the rest of them together were destroyed where they were. (131-2) So that was the fate of the eleven ships and their men, to be broken by rocks and fished for giants’ dinners. How sad is Odysseus about this? Recurring in these episodes are a pair of lines, saying how he and his men sailed on grieving at heart, ἄσμενοι ἐκ θανάτοιο, φίλους ὀλέσαντες ἑταίρους. Pleased to get away from death, having lost our dear comrades. It seems Homer delights in exploiting the new resonances which can be drawn out when lines of music recur, as when, in a song, the chorus returns with its same words newly illuminated after the injection of new verses. When these lines of transition first occur, after the debacle of the Cicones, Odysseus relates how his ships would not proceed before they cried out three times for each man lost in battle—six men per ship for twelve ships. But this time, there’s no mention of any mourning. The line above consists of two dependent clauses, both constructed from aorist participles, with no connecting particle or explanatory conjunction. Though there is no verbal prompt so to do, context in the earlier instances has suggested inserting a ‘but’ or a ‘though’ between the clauses: for example, ‘Glad to get away from death, though having lost our dear comrades.’ But with no mention this time that Odysseus’ remaining ship mourned the loss of the others, it becomes possible to hear the line in a new way: that the loss of that particular group of guys, was actually some part of the survivors’ pleasure. In Greek: [Allow me to recommend following along the Greek reading with a Greek text. My own edition of Books 9-12, with facing English translation, is available here [https://a.co/d/6JC0cRf]. All six volumes of my ‘Homer Odysseia’ are available on Amazon.] This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit homerist.substack.com/subscribe [https://homerist.substack.com/subscribe?utm_medium=podcast&utm_campaign=CTA_2]

Odyssey 10.1-79 Aeolus is often described as the ‘god of the winds’. Homer does not call him a god, however; he is simply Aeolus son of Hippotas. He is described as ‘dear to the gods.’ Virgil and others may have considered him divine, but for Homer perhaps he is more of an Elon Musk. Homer’s translators usually have Aeolus and his family living on a floating island. This is implausible, not because fairy tale wonders are by nature implausible—which is of course something to think about—but because Odysseus’ narrative seems only to make sense if Aeolus’ home is in a fixed place: one which can be left directly for Ithaca with the backing of a wind directed for the purpose, eastward out of the west, and also to which a ship could be blown straight back, if the wind becomes contrary. Translators must be yielding to the joy of the miraculous, as would I if there were permission; they are supported by uses in Herodotus which suggest ‘floating’ for πλωτός. Evidently Herodotus himself may have thought that Homer was referring to a ‘floating’ island when he used the word. That is some considerable authority. All the same, I think one ought to construe a verbal adjective in -τος, formed from πλέω or Homeric πλώω, ‘sail’, ‘travel by water’, and so render ‘sailable’, i.e. ‘reachable by sail’. Perhaps the sense is that one could only get there, or put in there, with the help of wind. The rock is supposed to be sheer right round the island. Possibly the use of oars would be useless in putting in there, as would have been the usual practice in landing on a beach. And of course the traversal of the ocean to the place would only have been possible by wind and sail. The futility of oars is patent after Odysseus and his men’s second departure from the Aeolian Isle: the spirits of the men were worn out by ‘grievous rowing (εἰρεσίη, 10.78),’ in the absence of an escorting wind. The use of εἰρεσίη, ‘rowing’, at the end of the episode, may serve to contrast the initial sense of Aeolus’ island as πλωτός: sailable only. But the fabulous floating island now lives a cultural life of its own. Aeolus is a weirdo. He is as isolated as the Cyclops, seemingly with no neighbours at all, though there is the briefest, largely inexplicable mention of a ‘city’ (πόλις, 10.13). I suppose there must have been a supply of servants, cooks, and farmhands. Someone to change the sheets. Unlike the Cyclops, Aeolus has a wife—Eve to his Adam, with whom he has had twelve children, six of each kind. We do not hear the story of his exile, if that is what it is; he’s somebody’s son, but we don’t know where Hippotas was from; perhaps his role as “storekeeper of the winds (ταμίης ἀνέμων) … Both to pause and to rouse the one that he wants”, was granted Aeolus by the son of Cronus as some kind of compensation for his brazen island imprisonment. But he does not appear to have the means—a ship or working crew, or dock—or the desire—to use that power to get wherever else he might want to be. The coordinated incest of Aeolus’ children seems to be their father’s choice, rather than something forced on them in their isolation. The family is forever feasting, and in case we may be reading something alien into practices that were not meant to be offensive, Homer rather rubs our nose in it—in his inimitable way, not by saying something out loud but by focusing our gaze: in this case, on the fact that after the party, when night came on, the sons would sleep with their ‘bashful wives’, and ‘go to bed wrapped in blankets, and in perforated bed frames.’ The poet does not need to say anything more to let us know that they quite enjoyed each other’s company, brother and sister, within those blankets and beds. In traveller’s tales, one should expect strange, titillating or offensive practices in exotic lands, which both tickle and shock the system for the kind of special pleasure such tales afford. Still it is hard at this distance to gauge the difference between what is odd or merely interesting, and what offensive. Sexual peculiarity, such as Polyphemus’ ovine bachelorhood, is to be expected. We shall discover, however, that Homer’s audience was quite as shocked as that of Sophocles’ Athens and Freud’s Vienna, at the thought of Oedipus sleeping with his mother. But what about Alcinous marrying his niece? Could that have been a brother’s duty upon her father’s passing away? Or a way to ensure the legitimacy or stability of his rule, and that of his descendants—a political motive? Alcinous’ brother, the king, had died without a male heir. Marrying his daughter preempts conflict. (In patriarchies, paternal uncles are generally rivals of one’s father for political legacy and bloodline. It is the maternal uncles who are ‘avuncular’. Odysseus gets his celebrated name from his maternal uncle.) All the same, one feels oneself on safe ground in registering the cosy intimacies of Aeolus’ sons and daughters as unsettlingly prurient, indulgently incestuous in such a way as to disturb one’s ease, like a false note in the soundtrack, through the whole brief episode. One does not feel this at all about Aeolus and his wife’s prolific fertility. It feels as though time has been suspended on the isle; that there will be no more children or grandchildren, that twelve is a full complement. There will instead be perpetual banqueting and cosy sex in their blissful prison. And no adultery: scandal in the Homeric world seems to centre on heterosexual adultery, where women play decisive roles. The sexual and political intrigues of Helen, or Aegisthus and Clytemnestra, together with the cosmic cuckolding of Hephaestus by Ares and Aphrodite, provide a background to suspicions about Penelope. The world of classical Athens, however, which first inherited the Homeric poems, seems heterosexually unstoried, and taken more with male homosexual intrigue and its political consequences—first in the days of the tyranny and then in the era of Alcibiades and Socrates. For Odysseus’ philandering, the punishment, as Jane Austen once put it, ‘is less equal than could be wished.’ Through all his tale of wanderings, and earlier to the smitten Nausicaa, he never lets on that there may be wife and son at home, still less that they are his home, and the main reason he so desperately longs for home. In the Iliad he is once actually called the ‘father of Telemachus’, uniquely among all the warriors with patronymics. Odysseus is very much a man who speaks, and forcibly suppresses others’ speech, on a need-to-know basis. To be fair, he only seems to sleep with ‘available’ goddesses. Odysseus and his men continue to display their outward exhibition of inner psychic tensions. One might say the so far nameless men function as projections of Odysseus’ inner subversion. How else does one take his assertion of vigilance, that he kept hold of the sail’s guiding rope to harness the wind sent by Aeolus, never yielding it to another member of the crew, so that they all might the soonest get to Ithaca? The curious phrase which I translate the ‘sail’s foot rope’, πόδα νηϝός (‘ship’s foot’ or ‘heel’) refers to a contrivance to allow manipulation of the sail. (In later Greek such a phrase would be translated ‘keel’.) The physics of wind and sail, and perhaps their metaphysics, are very much on the poet’s mind. A helping wind is not enough for a human being, these are not Phaeacian boats guided by thought; the sail has to be worked or misdirection ensues. Odysseus grasps his ‘ship’s foot’ exclusively, until he doesn’t. Just when Ithaca comes into sight, the men tending the home fires already visible, sleep gets the better of the pilot. Freud’s caretaker of consciousness lets his guard down, and his suppressed inner impulses overcome the sleepwalker. On all their adventures since leaving Troyland, Odysseus has been meticulous about dividing the booty equally among the ships. His personal benefits are modest: he is given an extra goat, he gets to eat the Cyclops’ ram. But the narrator, who is indeed Odysseus, exposes the suspicion that his pretence to equity hides the bulk of his haul from Troy itself, which is evidently hidden in his hold somehow, but known to all. It seems at Troy Odysseus was a chieftain, a minor nobleman; but in the aftermath, on the way home it seems a kind of democratic distribution has set in, and his former peasant soldiers have learnt to grumble. Now what’s he hiding in the ox-skin nutsack he got off Aeolus? Let’s get our share! And all is lost. Upon waking Odysseus is suicidal. There are several occasions in the story when this may be the case, but here it is explicit: … I debated, Whether I fall out of the ship and perish in the deep, Or I endure in silence and continue still among the living. (10.51-3) He carries on. They arrive back on the Aeolian Isle with Odysseus at his most pitiful and weak. He explains to his erstwhile hosts: “They blinded me in the mind! Bad comrades and, and not only them—Sleep! The bastard. But heal me, friends: for the power is in you.” Doesn’t even sound like him. Is he playing the supplicant or being one? The reaction he gets from Aeolus is perhaps the most vehement rebuke in all of Homer. I mean this objectively, in that Aeolus’ anger and disgust is rhythmically and harmonically obvious. There is only one dactyl in his opening line, spanning the mid-line caesura; everywhere else the two shorts have been substituted by a long, so we get a relentless sequence of long expletives: ἔρρ’ ἐκ νήσου θάσσον, ἐλέγχιστε ζωόντων · [In bold are the hexameter’s downbeats.] More than this, the Greek law of tonal prominence reveals that in almost every instance in this line, it is the upbeat of the foot which is tonally emphatic rather than the downbeat. : ἔρρ’ ἐκ νήσου θάσσον, ἐλέγχιστε ζωόντων · [In bold now are the tonally emphatic or ‘stressed’ syllables; only once (θάσσον) is the downbeat rather than the upbeat reinforced.] “Fuck off out this island—and quick, you most detestable of all things alive!” I confess I don’t quite understand the severity of his reaction to Odysseus’ return, which is extraordinary in all of Homer for its musical impact. But I will say that because of this story it has become a superstitious habit in my life, not to turn back, if I’ve forgotten something for example, once I’ve set out on a trip. Even if you’ve forgotten your phone or your bottle of water, don’t go back in the door. Never come back for a second helping of help, is that the lesson? Aeolus is offended as though there had been a threat to his authority, or to its basis in Zeus’s dispensation, or to the very nature of things. Or is there something wrong in general about heading back home in a straight line—for a ‘man of many turns’ (πολύτροπος)—and something even wronger about expecting to be able to get that chance twice? If Odysseus’ explanation for showing up again on their doorstep, the mischief of his crew while he fell asleep at the wheel, expresses an individual and collective psychic imbalance, as I have suggested, perhaps he is wrong to think that his dismissive hosts would have had the power to heal him. What does it mean to control the winds? Harnessing them is all we are good for. Winds have never been well explained, just like the clouds, which stay up though they are much heavier than air. Explanation of causes has never been a strong suit of the modern style of science. Serious people, although not children, live satisfied with the idea that heaviness, such as the heaviness of a cloud, is caused by ‘gravity’. Nothing out of Aristotle sounds stupid like that. It’s like saying clouds are caused by cloudiness. The winds blow, and we know not whence or why. In Greece, the winds have proper names: Boreas, Zephyrus, Notus, Eurus. They come from directions and give direction. Classical physicists talk of temperature, pressure, convection and the like. More interesting explanations will be likely when all these measurable factors are seen as side effects of electric currents and magnetic fields, in a solar or otherwise cosmic circuit, their directions as tangents to vortices. But what is electricity, what magnetism? How does polarity—especially repulsion—work? Hurricanes and tornadoes must be watched for, not generated or controlled, as surely as the auroras and volcanic discharges or the subterranean lightning which quakes the earth. We have devised many powers over nature, to be sure, profound technologies which we do not understand apart from the tasks they are able to effect. But we are not stewards of the wind. A gently zephyr flutters an eyelid, and a woman falls in love. Fate hatches. Homer can be an antidote for the childish pretensions of science, and its ‘laws of nature’. In that sense he is a light for an Homerist to carry in these Dark Ages. Homer has no word for ‘nature’. When it comes to that, how do we users of usage define what we mean by that word? Is there any way to do it without using the word ‘nature’? Something blindly dumbfounding, like a religious mystery, lies behind the catchwords in the cult of Science, like ‘nature’ or ‘instinct’ or ‘force’. The word translated ‘nature’ among the later Greek writers is φύσις (physis), derived from φύω, ‘grow’, ‘put forth’. A φυτόν is a plant. φύσις, broadly ‘growth’, occurs only once in Homer, in a passage we shall soon encounter. Its translation ‘nature’, from Latin, points instead toward birth. No such concept seems to operate in the way Homer paints the world. The closest one I can think of is the notion of μοῖρα, often in the phrase κατὰ μοῖραν (kata moiran), as here: ‘I recounted him everything in order (κατὰ μοῖραν).’ I have translated it freely in context as, for example, ‘by the book’ or ‘according to the recipe’. Μοῖρα freestanding means ‘portion’, and often needs to be translated ‘fate’ or ‘Fate’. In context it points to some kind of order that seems appropriate to a situation, which exerts a pressure that it be followed. Evidently, Odysseus’ return to his doorstep, after Aeolus had entrusted him with a sack containing the (unhelpful, one presumes) winds, is completely out of order. One might almost say against nature, as we also say about incest and celibacy. Aeolus invokes θέμις (themis), perhaps ‘lawful custom’, an idea which overlaps with κατὰ μοῖραν: “For it’s not a done thing, for me to help and to send off The very man who is despised by the blessed gods: Get out! Since as one despised by the gods you reached this place.” Odysseus has indeed made himself despised of at least one god. Can he be redeemed? Is the power in him (or us)? Will he one day fulfil his nature? Or are all these ways of speaking, a mathematics alien to both his causes and their effects? A man of many turns is, among other things, a thing like the wind. Or as mathematics, a human invention That parallels but never touches reality, gives the astronomer Metaphors through which he may comprehend The powers and the flow of things: so the human sense Of beauty is our metaphor of their excellence, their divine nature: — like dust in a whirlwind, making The wild wind visible. —Robinson Jeffers In Greek: This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit homerist.substack.com/subscribe [https://homerist.substack.com/subscribe?utm_medium=podcast&utm_campaign=CTA_2]

Odyssey 9.506-66 (end) A lot is made of Odysseus’ second vaunt to the Cyclops when he’s already escaped and on board ship. And rightly so; the cry of “I am Odysseus, City-Sacker” seems more of a revelation than the one we’ve just witnessed, in reality so to speak, when he tells his name to the Phaeacians before embarking on his story. This one almost seems to be Odysseus’ entrance upon the stage of history, as a soloist, rather than as part of the supporting cast of the Iliad. There is a tonal aspect to this outburst, which is in fact like an operatic signature line, a recognisable melody for an Odyssean ejaculation: Κύκλωψ, αἴ κέν τίς σε καταθνητῶν ἀνθρώπων ὀφθαλμοῦ εἴρηται ἀϝεικελίην ἀλαωτύν, (9.502-3) “Cyclops, if there’s any death-bound human being Should ask after the ugly blinding of your eye …” Notice especially the first half-line, which involves a changing pitch on every syllable (rising or falling or both on the same one), and ends in three, consecutive, acutely-accented long syllables: Κύκλωψ, αἴ κέν τίς σε. Such a sequence is exceedingly rare in Homer, to the point where it is identifying of Odysseus. It bears repeating that the nonsense taught as fact in Classics departments requires that these tonal patterns do not matter in composition; the oral theory of Homeric composition is based on purely metrical formulas, and ignores all the pitch accents. It is like a theory of Mozart which pays attention only to the lengths of the notes, and ignores all their pitches. This same sequence has already occurred earlier in the scene, when Odysseus expresses his indignation that the Cyclops must think him a fool, if he expects him to try to run out the cave entrance to be caught, as soon as the giant lets his sheep out to pasture: οὕτω γάρ πού μ’ ἤλπετ’ ἐνὶ φρεσὶ νήπιον εἶναι. (419) “For I suppose he expected me, in his mind’s vessel, to be such a simpleton.” Once again we see the same sequence of accents in the half-line, culminating in three straight long acutes: οὕτω γάρ πού μ’ ἤλπετ’. I have written on this and other ‘signature lines’ discovered in the tonal patterns of Homer’s compositions in my recent book, Singing Homer’s Spell (available here [https://a.co/d/1SPuPh6]). I shall have more to say on this matter after we reach Ithaca. But there is a third and final outburst from our hero, which, it seems to me, deserves more attention than most are inclined to give it. It expresses, in most certain terms, Odysseus’ wish for himself and for the Cyclops: αἲ γὰρ δὴ ψυχῆς τε καὶ αἰῶνός σε δυναίμην εὖνιν ποιήσας πέμψαι δόμον Ἄϝϊδος εἴσω, ὡς οὐκ ὀφθαλμόν γ’ ἰήσεται οὐδ’ Ἐνοσίχθων. “If only I had the power over soul and life To castrate you, and send you into Invisible Hades’ house, As surely as he will not heal your eye, not even the Ground-Shaker.” Odysseus wishes that he had the power to make an eunuch of his rival, before killing him; and measures the energy of this wish by a parallel wishful expectation, that Polyphemus’ eye will never be healed even by the power of god. This is his final statement to Polyphemus, and it is tempting to see it as a culmination, like the third of three long acute syllables. Draughting on Homer’s authority in psychology, perhaps one should see the castration of one’s rival as an archetypal masculine wish. Freud, taking no small cue from what, by his time, had come to be called ‘Greek Mythology’, places an emphasis specially on castration of the father as an innate or developmental wish of a son. It does not seem likely that the Greek theogony, where castration of the father was essentially the method of royal succession for the chief masculine god, was absent from Homer’s imagination. Zeus is often addressed in Homer as Κρονίδης, Cronides, ‘son of Cronus’, so that whatever was known or believed about their history in Homer’s consciousness and audience, the conquest and succession of Zeus over his father to establish a new world order is an ever-present in the rhythm of Zeus’s patronymic. Also tapping into the ambient reality of this revolutionary succession is the non-visible presence of Atlas the Titan, apparently still actively holding the structural pillars of the cosmos which keep apart the earth and sky. His daughter Calypso is visible enough; her fair tresses are kept cloistered on an island at the navel of the sea, apparently to prevent her mating and having fearsome offspring. Even the unstated threat to Zeus of a seemingly disgruntled figure like Poseidon, where the business of the Odyssey has to be stealthily planned in the latter’s absence from Olympus, adds to a certain instability in the foundations cultivated by Homer to work like sinister music in his background. Who knows what cosmic strings have been pulled when Odysseus blinds Poseidon’s son? Odysseus is messing in the margins, sleeping with dangerous women. Still I would suggest that castration of the rival is a broader and deeper drive which also encompasses Freud’s castration of the father. Perhaps we should credit Homer with the dramatisation of a psychoanalytic insight. The third outburst of Odysseus unmasks his deepest compulsion and desire. Castration of the rival speaks to men’s experience and behaviour in sports, war, and politics, oligarchies, tyrannies and corporations, the entertainment industry and holy conclaves. It also speaks to women’s empowerment over men, in ways we shall immediately encounter with Circe. Although I cannot prove this, it seems to me to be reasonable to suppose that the μοιχάγρια (moikhagria), the ‘adulterer’s ransom’ (8.332) to be extracted from Ares by the cuckolded Hephaestus, includes his balls. Singing Homer is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. It may be instructive to view the three outbursts of Odysseus as a progression. Indeed, they are more a descent into Hell than a pilgrim’s progress. Consider the first of them: “Cyclops, it didn’t turn out, did it, that they were comrades of a cowardly man To be ate in your hollowed cave by means of strength and force. Get a load of what comes on yourself—shitty results, You bastard! Since you did not scruple with strangers in your own home, To eat them up! That’s why Zeus paid you back, and the rest of the gods.” The magnifying of his own power yields in this instance to Odysseus casting himself as a justicer, an agent of Zeus’s Justice. A friend who grew up in North Carolina told me of a primary school teacher who, before she administered the ruler to a whimpering child, would say, holding her hand to her heart: “This hurts me right here.” What was done to Polyphemus had to be done, because he violated the culture and tradition now celebrated for the Homeric Age, of guest-friendship. It does not matter that figures like Odysseus and Menelaus appear to exploit the privileges expected to be afforded the stranger and guest, as an opportunity to ‘get something’. Odysseus is explicit about his motives for trespassing into the cave of a giant ogre. ‘What if he gave me a guest gift?’ (229) And he ill-advisedly invokes Zeus to Polyphemus, as part of his attempted shakedown: “We, however, approach these knees of yours As suppliants, in hope perhaps you give a proper guest gift, or otherwise You offer a present, which among guests is the custom. But respect, oh mightiest one, the gods: we are your suppliants, And Zeus is the avenger of suppliants and guests, Zeus Guest-Friend, who goes alongside respectful and respected strangers. (266-71) Of course the Cyclops is triggered by the invocation of Zeus. But it is a conceit of the avenger that he is actually a justicer, passive to the force of law and decency which is the tradition of guest-friendship, so that Odysseus’ acquisitive motives fade from view. It is not Odysseus, but Zeus and the rest of the gods who have paid the Cyclops back. The city-sacking pirate’s invocation of justice, is all the same and nevertheless an invocation of Justice. It is different in kind from the two following ejaculations of Odysseus toward Polyphemus. One way to see the progression is as a successive unmasking of the man’s true motives. Justice is, at some level, other- and community-centred. From the dispassionate appeal to the decency of guest-friendship rituals guiding human beings in their most vulnerable interactions— harbouring the golden rule amidst the provisional fairness of expected reciprocation—in the face of the Cyclops’ brutality and cannibalism—we move to pure and spirited self-centred assertion: I’m not nobody, I’m Odysseus City-Sacker, Laertes’ son from Ithaca. Finally we come to the fully expressed wish from the gut: to castrate and then kill his rival, and further, that his wounds remain an unhealed, living torture. In response to the first outburst, where Odysseus says Polyphemus is being punished for his sins as a host, he has no words, he gets angry and hurls a rock. To the second outburst, when he learns Nowan’s true name, Polyphemus recalls a prophecy that an ‘Odysseus’ would cause him to lose his vision. He had been expecting a mighty warrior, not a puny Ithacan. Now, in response to Odysseus’ castration wish, he calls to Poseidon in prayer—one imagines this is a new posture for him—and adds a provision that seems to seal Odysseus’ fate: “Let him come ill and late, having lost all his comrades, On a foreign ship, and may he discover calamities in his home.” (534-5) We have heard some of this before; in the old man Halitherses’ reading of a bird omen, at the assembly called by Telemachus in Ithaca (Book 2), he details the phrase “having lost all his comrades,” so that their repetition here has the effect of a kind of confirmation. There Halitherses spoke ominously about the “twentieth year.” It helps also that we already know that all these wishes of Polyphemus will come true. Odysseus’ fate takes its final shape in this very moment, this very utterance of the Cyclops. Now, Homer begins the Odyssey with Zeus’s speech declaring that the adulterer Aegisthus has accomplished acts ‘beyond fate’. This is a radical formulation which undermines both the artwork and the cosmology of the Iliad. To put it simply, there are new rules for the inevitability of ‘fate’, what is fated, in this poem. One might presume that the concept may have become meaningless. When Halitherses shares his prophecy in Ithaca, upon reading a bird omen, he is met with the snarkiest scepticism from the suitor Eurymachus. “Birds? There’s rather a lot of them, under the rays of the sun, Busy here and there; and not all of them mean something …” (2.181-2) Modern, consumerist Ithaca has fostered an altogether modern attitude toward tradition and religion. So how is it that when one hears Polyphemus’ prayer, one all the same feels that Odysseus’ fate has been locked into place? Where does such a conviction come from when Homer appears to disown, on purpose in the Odyssey, any simple kind of fatalism? In one sense, skepticism inside a drama generates its opposite; that is, a certain character’s disbelief serves to frame the beliefs and utterances of other characters as true, and possibly portentous. The true prophets in the story are only proved so in the outcome, but one develops working hypotheses about whom to trust and how things will work out. At the end, one prides oneself on having being right about which characters had proved to be insightful. I believe that the repetition of phrases plays a key role here. The irony is not lost on me that the repetition of phrases in Homer is still generally thought to be a slightly unfortunate necessity of the exigencies of an improvised, oral composition, rather than a matter of musical choice. These phrases are not, however, ‘metrical building blocks’, as a directly ontological matter. They are fully fledged combinations of word, rhythm, and accentual melody, snatches of song which imprint on the memory in the way that lines of song do, so one sings rather than quotes them. There are more than one significant series of lines which recur like refrains through the Odyssey; we have met one already, in the description of Penelope weaving and unweaving her web by night. Another highly enigmatic one is to come from the ghostly lips of the prophet Tiresias. These lines recur from different mouths and in different contexts, thereby gaining a kind of independent objectivity. The effect of such passages is, to my mind, very much like the return of a chorus between verses of a song, a chorus which takes on new meanings and resonances—though the words and melody remain nearly the same—as the song’s story develops through the changing verses. The first return of a sequence of such lines magnifies them in such a peculiar way; they become infused with a sense of inevitability, including the inevitability that they will again be sung. In the Iliad one gets the sense that every single death is a fated thing, a moment of human naming when a cut thread dangles in air, like a finished film passed through the projector and flapping on the spool. This Odyssey poet, on the other hand, seems knowingly to have set himself a challenge by gaming the inevitability of fate. Yet this poet proves masterful all the same, among all poets, in creating a sense of inevitability, and the repetition of phrases and passages is surely a key to this profoundly musical achievement. The sense that Odysseus’ fate has been sealed in Polyphemus’ prayer is felt and deep. The drama and the posture of the performer, voicing the irreligious Polyphemus now reduced to prayer, must play a role in the effect. I don’t pretend to understand how all this works, except that certain reechoed phrases become sonorous touchstones which lock the words and their implications into place somehow, so that time itself seems to rhyme. I welcome suggestions. If one reverses the order of Odysseus’ outbursts to the Cyclops, a recognisably Platonic progression can be formulated. The initiate proceeds from the reptilian screech for castration and death, the urgings of the lowest, tyrannical part of the soul, back to the spirited assertion of identity, self, and origin: “I am Odysseus the Ithacan City-Sacker, Laertes’ son.” Finally, back at the summit, there is the appeal to justice, and a social and cosmic order higher than the self. This is the world of Zeus Xenios, Zeus of the Guest-Friend. The appeal to justice is also an appeal to the rational part of the soul. This rational part is sometimes imagined as a third eye. (See the representation of a Cyclops above). Odysseus’ fateful psychic descent to hell becomes, in reverse, a pilgrim’s progress to the opening of an eye. Allegorists were among the first literary interpreters (and defenders) of Homer. Unfortunately allegorical readings can seem heavy-handed and reductive. Unlike the poem that the pedagogue seems keen to replace, his reading of it lacks nuance and above all, rhythm—and melody. All the same, it seems undeniable that there is a psychic progression depicted, artfully and intentionally, in the three successive ejaculations of Odysseus to the Cyclops, although it also seems intentional that the progression is in reverse to the sensibility of any sort of moralist. It also seems unavoidable that a Cyclops be symbolic of something on his own, in his name and in his nature. (He is a ‘Circle-Eye’, perhaps a ‘Circle-Face’.) Mind you, it would seem to make all the difference if one envisions him as monocular—that is, deficient in some way—or as someone with a sort of third eye. But either way, conquering whatever the giant Cyclops represents, seems to demand interpretation and exegesis. Homer certainly attracts pedagogues and moralists. Poly-Wily Homer may, however, take some delight in booby-trapping them. Consider again, for example, the progression of the Cyclops himself in his own three stages of conversation with Ulysses. It is not a descent but an ascent. To Odysseus’ moralising about Polyphemus’ punishment, the latter has no words, and hurls the top of a mountain in anger. Next in response to Odysseus naming himself, he (funnily enough) confirms that name, as a prophesied one—although, surprise, his conqueror turned out to be an Ithacan nobody. In return he claims his status: in his own moment of spirit and self-assertion, he suggests that it is the Earth-Shaker himself who boasts of being his father, not he of being Poseidon’s son! But in response to Odysseus’ wish to castrate him, the Cyclops, perhaps for the first time, directed his voice upwards, toward the sky, and ‘Started praying, his arms stretching out toward the starry heaven:’ (527) It is of interest that Poseidon is also to be found amid the stars in the sky, not in the earth or like Neptune in the sea. ‘Circle-Eye’ also suggests a celestial visage. Polyphemus’ journey in this interaction goes from blind rage, to boastful and competitive self-assertion, at last to an upward embrace in prayer which bespeaks an awareness of the actuality of his place in the world. In his finally humble, and humbled, position, looking up at last to powers he acknowledges to be higher than himself, the Cyclops’ prayer turns into true prophecy about what Odysseus’ journey will have to entail. While it seems that he means the prayer as a curse upon Odysseus, consider that he imagines his wish, that Odysseus never gain home, not being fulfilled: the delayed journey on an alien ship with the loss of all his men, to a home in trouble, is based on the premise that it be Odysseus’ fate—bodied forth in the Cyclops’ imagination in its full refrain— “… to see his friends and to reach His well-built home and the mother earth of his fathers …” (532-3) It is odd to register these words from the Cyclops’ own mouth, as part of the Cyclops’ prayer. In contrast to Odysseus’ descent into kinetic savagery, Polyphemus has come to a moment of still awareness. ‘Stretching out’ in the line above translates Greek ὀρέγω (oregō); Aristotle uses this verb, in its middle voice, in the first sentence of his Metaphysics: ‘All men desire [reach themselves out towards] knowing, by nature.’ (980a21) Perhaps it needs saying: the brutal Cyclops is a man like us. “I stumbled when I saw.” Is Odysseus’ story a journey of the soul? Homer leaves many signs that this is so, even more as we proceed to Circe’s Isle and the Underworld. Each episode seems a test and an initiation. Odysseus began with a sleep like death under the entwined olive bushes, to wake up to Nausicaa. Arete says he shall ride the Phaeacian ship overcome once again by ‘sweet sleep,’ before he wakes up in Ithaca. The escape from the Cyclops is an escape from death’s cave. Rebirth recurs like the days of the sun. When Socrates tells his own story of the soul’s journey to the Underworld, in the myth of Er in Plato’s Republic, he makes allusion to the ‘Tale of Alcinous’, an ancient name for the story Odysseus tells in Alcinous’ palace. This story is evidently his model, and the shade of Odysseus plays a starring role in Socrates’ story of the soul’s choice of pattern for the next life, based on her experience in this one. Plato, at any rate, seems to have heard Odysseus’ story as just such a soul’s journey. His entire Republic is a first-person narrative, like the Tale of Alcinous, where Socrates both does the narration and plays all the parts. To be sure, there were elements of the power of the Homeric performer’s mimesis, a protean ability to project seeming truth, which must have terrified Plato; but not enough so as to not attempt it himself, with the role of Socrates in the one-man show called the Republic. By itself, Plato’s response should alert us to attend, all remaining eyes open, to our initiate’s path as we follow Odysseus in the Odyssey. Escape from the cyclopean cave was already a layered thing in Homer’s hands, before Plato got hold of the idea. Socrates famously bans Homer and the poets from the ideal city in the Republic. Yet Plato quotes Homer extensively in that book, so that the Republic is by far our greatest source of fragments, and means of confirming the much later Alexandrian texts. The Republic itself, as opposed to the ideal city described in it, is, in effect, a curated distillation of all the best and most naughty bits in Homer—which ought to get the Republic itself banned from there as well. As my sometime teacher Allan Bloom used to ask: does Plato or doesn’t he, want you to hear Homer? I came to Homer in graduate school in Chicago as a student of Plato’s Greek. What I discovered there, is what now seems to me to be the true sun outside Plato’s cave. Of course Socrates paints Homer as one of the gaolers and shadow-masters within. But the allegorists were on to something. It is not so much a matter of reading between the lines, as paying attention in detail to their movements, and singing them. In Greek: This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit homerist.substack.com/subscribe [https://homerist.substack.com/subscribe?utm_medium=podcast&utm_campaign=CTA_2]

Odyssey 9.415-505 The thing is, Odysseus is a bit of a nobody. He announces himself to the Cyclops as ‘Odysseus the City-Sacker’ (Ὀδυσσεὺς πτολιπόρθιος). That does sound like something. But ‘son of Laertes’? ‘Who has his home in Ithaca’? Laertes is an old man who has retired to potter around in the country, too feeble even to think, it seems, of defending or managing his son’s property. That Penelope purports to be weaving a funeral shroud for him rather suggests that death is all that is immediately expected of him. That her intent is actually a ruse only underscores the marginal stature of Laertes, and suggests a merely secondary interest on her part in his well-being. The old man never comes to town any more. He is one of the many constituents Odysseus has abandoned on his escapade to Troy. As for Ithaca, Telemachus tells Menelaus that it is a rocky place, unfit for the horses which his host wishes to bestow on him. From that day to this, horses have graced the nobility of men and women. Chivalry is horse-culture. Polyphemus the lonely Cyclops wishes his bellwether ram could talk to him, like a friend, but in the Iliad, Achilles’ divine horse Xanthus does actually talk, rejecting Achilles’ blame for Patroclus’ death and prophesying the hero’s own. But there is no place for horses—or, it seems, chivalry and the chevalier—in rocky, be-goated Ithaca. Odysseus is like one of those athletes who, in his moment of glory, shouts out his hometown and his parents (while he’s thanking Jesus). The footballer briefly puts Podunk, Oklabama on the map. Odysseus seems similarly keen to trumpet his origins. The culture of patronymics is aristocratic; only important people are announced this way in Homer. But the advancing of such a humble figure as Laertes, and especially the signposting of Ithaca, seem to me to have a tinge of the democratic sensibility in their wellspring. One take’s pride in one’s origins, regardless, in a democratic constitution. ‘City-Sacker’ is also an interesting one. Odysseus certainly has a claim to the title. But it has been rather pressed on us that Odysseus sacked a great city by means of a devious stratagem, not by his martial prowess. Indeed, the operation to disable the Cyclops would have involved considerable dexterity, strength, and teamwork, not to mention the risk from anything but complete success, even though the victim was already legless. The wooden horse, by contrast, emptied its soldiers on Trojans caught unawares, essentially in their pyjamas. The recounting of his deeds under these circumstances, by Demodocus at Odysseus’ request, has just reduced the perpetrator to paroxysms of grief. The simile comparing his tears to one of the many widows he has created, destined for slavery, suggests profound catharsis and perhaps remorse. I think it may be important to remember that the man now telling the story has just undergone this gruelling, self-imposed art-therapy, when he comes to the part where he announces himself to the Cyclops as ‘Odysseus City-Sacker’. That happened close to a decade ago, when he was still fresh from Troy, and attempting to pillage the Cicones. We recall that before arriving in Scheria, for most of seven years—after the initial euphoria of cohabiting with Calypso—Odysseus has spent his days alone on a headland of an island at the ocean’s navel, looking down at the sea in tears and groans. It is not impossible to imagine that the man longing for his wife and home, in bitter mourning for his lost comrades and purpose, was also suicidal about being a devious, cold-blooded city-sacker. Imagine Odysseus at a cliff’s edge. “How fearful/And dizzy ’tis to cast one’s eyes so low …” I find intriguing the story reported by Tacitus, that an inscription of Ulixes could be found by the Rhine in Germany, where he founded a city, which appends also the name of his father Laertes. Evidently this person was serious about memorialising his Dad in the same breath as himself, wherever he left his mark. Perhaps we may surmise that the ‘real’ Ulysses eventually came to be known as a city-founder, not a city-sacker. Odysseus shouts out three different messages to the Cyclops from on board ship. The fateful declaration of his name, parentage and origin constitutes the middle outburst. We shall consider their developing rhetorical sequence in the next reading. Here we observe certain patterns in the music and the action which, while deployed in the telling of a most unique and dramatic event, nevertheless bear Odysseus’ and the Homeric signature, both in the tale and the telling. Polyphemus twice throws jagged missiles at Odysseus’ fleeing ship. Both barely miss. The first lands in front of the ship and the second behind. Is the Cyclops now blind, or has he just lost his binocular depth perception? The effect is first to push the ship back perilously close to the Cyclops’ land, before the men are able to row with enough energy to pass beyond Polyphemus’ blind (or half-blind) trajectories, so that the swell from the second bit of crashing mountain hits astern, and pushes the ship forward toward the neighbouring undeveloped island full of goats. Behind there, the rest of Odysseus’ fleet has been hiding, a kind of sleeping consciousness through it all. In this sweeping motion backwards before proceeding forwards, I believe there is expressed an ethos of ‘epic’ motion. We shall see it recurring through Odysseus’ travels, on small and large scales. Earlier Menelaus had had to return to make sacrifices back where he’d come from in Egypt, before he and his men could escape starvation and the doldrums on an island, and finally proceed on their arrested journey back to Argos. I have argued that a dactylic round dance still performed in modern Greece provides the template for the dactylic hexameter; in the middle of the third dance step of the six, the dancers’ rightward motion stops, and they turn back to the left. There is a loop of retrogression, with the rightward movement resuming spatially where it had left off, at the beginning of the fifth step of the six. This circling motion forward to the east, with loops of westward retrogression when in opposition to the sun, is observed for the outer planets such as Ares and Zeus (Mars and Jupiter), present in our sky. I do not propose that there is anything allegorical or otherwise symbolic about this motion, only that its sense is pervasive, in the way that the form of a dance—a waltz, or a mazurka, or the twist—informs the music which it inspires and is energised by. Most every line of Homer reflects the turning points of the dance in its word divisions, which produce articulations in the metre called a caesura and a diaeresis. These two moments in the unfolding of an Homeric line frame the internal retrogression in the underlying onward circling. In Homer this motion bubbles up from the feet, if you will, into what could be called a musical as well as a narrative ethos. One does not go in a straight line from A to B, or head straight home. Rather, one circles there, with necessary retrogressions. ‘In life and in storytelling, as in dance, there is a correct way of returning by turning.’ To a great extent, however, one must understand the direct effect of the dance of the Muses to be sublimated, as it is also when orchestras play symphonies in dance rhythms while everyone, players and audience, remain glued to their seats. Odysseus, and Homer with him, have taken the origin of their rhythm into themselves, and stand before us as soloists, like Bach at a clavichord playing a virtuoso gigue. No one dances to Bach’s suites any more. Nor is it likely that anyone danced to a Homeric rhapsode’s performance. The recently dancing Phaeacians stay seated for Odysseus’ story. The rhapsode’s accompanying instrument was no longer a lyre; now he was armed with his cloak and a staff, along with his voice of course. (Odysseus the character may be wearing a sword, rather than holding a stick, which he won as reparation for insults to him during the Phaeacian games.) We see strong indications that the Odyssey has been scripted for such a performer—cloaked, and wielding a stick. Consider the moment when, after Odysseus’ first invective outburst, Polyphemus breaks off the top of a mountain and hurls it toward the boat. It just misses the steering oar at the front. ‘And the sea surged up because of the rock coming down: There she went, quickly toward the shore—borne by the back-flowing swell, A flood-tide out the deep drove her to reach the dry land. But I was there, grabbed in my hands a very long pole And pushed her off and sideways, encouraged the crew and ordered them To throw down with the oar handles, so we might escape out from evil, Signing with a nodding head: and they fell forward and set to rowing.’ (9.484-90) (Note that the word ‘back-flowing’ in line 485, παλιρρόθιον (palirrhothion), fills the portion of the hexameter line where the retrogression in the circle dance would have occurred.) How convenient that Odysseus found a “very long pole” just lying around there in the stern. I think perhaps the fact that a rhapsode comes with a staff in his hands, perhaps makes less implausible, in his telling, the sudden appearance of a conveniently long pole. Perhaps there would ordinarily be such a pole there at the stern, precisely for the purpose of pushing off into deeper water. But in Odysseus’ story, it certainly seems that he has just come up with it out of the blue, happily and fortuitously; and indeed, perhaps Homer has. The possibilities for supporting gesture become innumerable for a performer, once he starts looking for them. The actor pushes off with his staff, then nods his head in silent command. Suddenly he becomes a desperate oarsman with an oar. Are there not scripted cues here, for a thespian? The stick of olive with which Odysseus and his men dispatched the Cyclops’ eye, was only the latest opportunity for the Homeric performer’s choreographed use of his prop. It has been both a loom and a mast—the same word in Greek, ἱστός (histos), a thing ‘stood upright’—and it has been Athena’s spear and her magic wand. Indeed, in putting out Polyphemus’ eye, the vivid enacting of the various thrusting and spinning motions required may have contributed to a sexualising of the scene, which has left an occasional imprint in Homer’s diction. On the purely lingual face of it, these intimations can seem a little odd or obtrusive. Most remarkable is the line which opens our passage: ‘But the Cyclops, groaning and throbbing in the pangs of giving birth …’ Our word ‘travail’ allows translators to dodge the issue, because the English word need not refer solely to the labour of giving birth. This does not seem to be the case, however, for Homeric ὠδίνων (ōdinōn), taken here to be participial. This is shocking stuff, because it is sudden, brief, and not further explained, and the imagery is not a metaphor or part of a discernible simile. It does not appear to pay, for example, to ponder what it is being given birth by Polyphemus. Yet I can imagine that after witnessing the performer enact the putting out of the Cyclops’ eye, wielding his burning staff of olive, his pregnancy might well seem a tacit, semi-conscious consequence of the fact that Polyphemus has been, well and truly, fucked. On the question of who might compare pain of any kind to labour pains, and specifically how, I propose that there are scientific grounds for judgement. Labour pains, experienced only by pregnant women, are therefore unlike any other vehicle in a comparison. Homer compares the pain of an arm wound to Agamemnon to the pangs of labour, in such a way as to elucidate the quality of that pain (Iliad XI.269-72). On the basis of this usage alone—but also for other reasons—I can conclude that the composer of the Iliad was female. The direct use here in describing the condition of the Cyclops—implicating instead the stricken vulnerability of the woman, helpless and passive to unpredictable recurrences of intense agony—remind one of the usage in similes from Isaiah describing the debased state of Zion (13:8, 21:3). It strongly suggests that the composer of the Odyssey was male. I think it pays great dividends to imagine enacting the story of the Odyssey as you read it—that is, to imagine telling it to people present in front of you—perhaps while holding, or having ready access to, a staff. So I encourage you to do it. There is a feeling of seeing the poem from the inside, as I imagine an actor channeling Hamlet also channels Shakespeare. While bringing it to life, one may find, as I do, that Homer’s script regularly answers as an actor’s and a director’s prompt, seemingly by design. I note in particular that the sympathy typically aroused when speaking someone else’s speech, is surely a necessary foundation for any act of interpretation. This is not always obvious to students, critics, and other essay writers. Sympathy can sometimes seem to conflict with one’s ability to judge morally, generally by undermining it. But there must be sympathy for the Devil in John Milton, to speak him with such feeling. Such sympathy is surely second nature to producers of dramatic imitations, a field in which Aristotle claims Homer to be a pioneer (Poetics 1448b37). Homer himself, or Odysseus his present narrator, is putting himself in someone else’s place every time he delivers a speech. This goes even for the monstrous cannibal Polyphemus. When he is described as in labour, or he is madly hurling the tops of mountains at abusive voices over sea, we see him through the telescope as a demeaningly feminised yet terrifying villain. But in the troglodyte’s cave, his home, we experience him disarmed, dismayed, and dis-eyed. Odysseus gives him one of the most curiously affecting—and ludicrous—speeches in all of Homer. The Cyclops meets his bellwether ram as he heavily exits the open door to go to pasture. Odysseus, clinging on under his woolly belly, is in a position to hear everything. “Ah Ram, buddy, why do you hurry up this way through the cave—of all my flocks The last? No way before did you get left behind coming and going with the sheep, No! Far the first you’re nibbling on the delicate flowers of the grass, Strutting long steps; you’re first to reach the streams of the rivers, First home to the stall, longing to return Of an evening: but now? You’re last of all. Ah, you’re sad for your lord, You miss his eye! The one which the evil man completely blinded With his pathetic friends, once my mind’s vessels were defeated by wine— Nowan, whom I tell you has not yet escaped from his destruction. If only you could be of my same mind, and become someone to talk with, To tell where that fellow is skulking away from my power: In that case his brain, oh, through the cave this way and that Gets dashed on the floor from his pummelling, and my heart Would settle down from the evils which this nobody gave me—this Nowan.” (9.447-60) This man loves his pet! Who among us has not projected in this way upon the psyches of our animals? Of course we are narcissistic and perhaps delusional in so doing, but who will throw the stone, and deny his sympathy? Polyphemus is a man-eater who tenderly puts his lambs and kids to their dams. That is a capitalist who loves his dog. In point of fact, Polyphemus appears to be a cheese-loving vegetarian when he’s not eating man-flesh. By contrast, Odysseus and his men seem singularly focussed, after their escape, on the animals the Cyclops tends and loves, as so much mutton to be driven and stolen. This goes even for the ram who saves Odysseus’ life, who becomes the captain’s special, edible prize. Though from the human angle Polyphemus is a lawless solipsist, for his sheep and goats he is a benevolent ruler who studies their nature and their joys, and regulates their lives in accordance. The sympathy Odysseus summons to speak as Polyphemus is overwhelmed by the sympathy of Polyphemus himself, who seems to live vicariously through his ram. This first among sheep normally leads his fellows the pastoral way to the delicate flowers and the rivers’ streams, but lingers now the last of all. The brutish Cyclops leaks that he also has learned to love the flowers and the streams. Of course he must be missing my eye, says the pastoral Cyclops, just like I do! Sympathy is reciprocal. When Polyphemus feelingly evokes the ram’s “longing to return” to his stall in the evening, any disdain of him devolves also upon the animating pathos of the Odyssey itself. Homer not only looks through the Cyclops’ eyes, he looks through the eyes of a domestic ram and finds an Odyssey in his daily orbit, and its hesperian longing. But apparently within the ram, Homer reaches a limit of his powers to bring thought to speech. One wonders what these limits are in the storyteller, of sympathy and imagination? Perhaps Homer could have given voice to the ram. But could a ram play the ewe? In his wish that the ram could talk, however, Polyphemus goes even further than sympathy: he speaks of them ‘being of the same mind’, ὁμοφρονέων (homophroneōn), a word which Odysseus had once coined in his own person. This was when he first confronted Nausicaa, emerging naked from a bush. Odysseus wishes for her, and her future husband, that the gods grant them this quality, ὁμοφροσύνη (homophrosynē), ‘oneness of mind’ (6.180-5). It seems to me that ‘sameness of thought’ may refer to something different from, though not alien to, ‘togetherness of feeling’ or ‘of experience’ (sympathy). This is Odysseus at his most naked and truthful, wishing for Nausicaa truly the best thing that he knows. It is, to me, stunning—stunningly perceptive—that he imputes this thwarted wish for communion to Polyphemus, his nemesis. We see them together in Homer’s iconic figure: the man underneath, clinging to the ram’s magnificent fleece, heart to beating heart. But they are man and mutton, not soul and soul or mind and mind. If to hear this wish for oneness of mind from the mouth of the Cyclops, meant for him and his ram, is intended to be mocking of him, then it is painfully so. This creature is terribly alone. Even his neighbouring Cyclopes cannot understand what he’s saying, to his considerable cost. His imagining Sir Ram coursing the fields with long strides, μακρὰ βιβάς (makra bibās), like a noble steed, or Achilles, is faintly ludicrous for a sheep. But again, it is painfully mocking. If we proud modern individuals are different from this Cyclops, then it behooves us to figure out how—though we travail. My brain I’ll prove the female to my soul, My soul the father, and these two beget A generation of still-breeding thoughts, And these same thoughts people this little world, In humors like the people of this world, For no thought is contented … Thus play I in one person many people, And none contented. Sometimes am I king. Then treasons make me wish myself a beggar, And so I am; then crushing penury Persuades me I was better when a king … … But whate’er I be, Nor I nor any man that but man is With nothing shall be pleased till he be eased With being nothing. (Richard II, V.5. Played by Sir Ram.) In Greek: This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit homerist.substack.com/subscribe [https://homerist.substack.com/subscribe?utm_medium=podcast&utm_campaign=CTA_2]