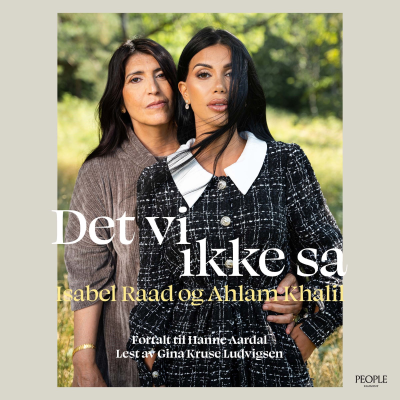

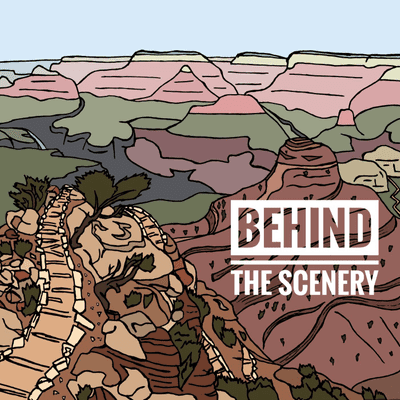

Behind the Scenery

Podkast av National Park Service

Tidsbegrenset tilbud

2 Måneder for 19 kr

Deretter 99 kr / MånedAvslutt når som helst.

Mer enn 1 million lyttere

Du vil elske Podimo, og du er ikke alene

Rated 4.7 in the App Store

Les mer Behind the Scenery

Hidden forces shape our ideas, beliefs, and experiences of Grand Canyon. Join us, as we uncover the stories between the canyon’s colorful walls. Probe the depths, and add your voice for what happens next at Grand Canyon!

Alle episoder

55 EpisoderCanyon explorer/hiker extraordinaire. Noted Grand Canyon book author. Family guy. And medical doctor to Grand Canyon National Park. Join us for an in-depth, fun, and at times personal interview with a fascinating human being: Dr. Tom Myers. Also, learn who is really to blame for many of Grand Canyon’s medical incidents, injuries, and mishaps! --- TRANSCRIPT: --- ♫Guitar and singing: ♫Hiking away again in Grand Canyon, ♫Searching for my elec-tro-lytes (salt, salt, salt), Dr. Myers quote (Sometime it's on the path it's on the path most rocky that you will find your footing most true.) ♫Some people claim, there’s a Ran-ger to blame, ♫But I know, it’s my own darn fault. Grand Canyon. Where hidden forces shape our ideas, beliefs, and experiences. Join us as we uncover the stories between the canyon’s colorful walls. Probe the depths and add your voice for what happens next at Grand Canyon. Hello and welcome. This is Jesse. This is Emily. And this is: Behind the Scenery. “Hiking Away again in Grand Canyon.” Indeed! How about completing 300 Grand Canyon hiking/backpacking trips? How would you like to spend over 1000 days hiking/exploring below the rim? How about releasing a new 430-page book about your seven-year quest to hike the entire length of the Grand Canyon? A though-hike feat accomplished by maybe around 60 people only, in modern history? Oh, let’s also throw in over 40 Grand Canyon Colorado River raft trips? And a couple other Grand Canyon books, including the best-selling: Over The Edge/Death in the Grand Canyon book. 600-pages! Lists all know fatal mishaps in Grand Canyon. Sold over ¼ million copies! All of this, on your own time. Hello. My name is ranger Doug. I am a summertime park ranger at the North Rim of Grand Canyon National Park. I would like to introduce you to Tom Myers. He is the dude who has accomplished all of the above. But wait. There’s more. Actually his full name is Doctor Tom Myers. Yes, you guessed it, medical doctor Tom Myers. That’s his day job: Doctor to Grand Canyon National Park. Since 1990. Yes, there is a medical clinic on the South Rim of Grand Canyon National Park. On call 24/7. Seeing patients, many of whom are having the worst day of their lives. Over time, Dr. Myers has become an expert in understanding heat-related problems. Currently he and his wife Becky live in Flagstaff, Arizona and have three grown children and two grandchildren. In late May, 2025, Dr. Tom Myers came to the North Rim of Grand Canyon National Park, as a guest speaker. To deliver a public talk and slide program titled: Lessons from Life and Death at Grand Canyon. While visiting the North Rim, I thought it might be nice to have a conversation with this fascinating man. I invited him to join me for an in depth, wide-ranging and at times personal interview … looking into his life and park experiences. You are in for a real Grand Canyon treat. Dr. Tom Myers, come on in. Join me. Welcome. Dr. Myers: My name is Tom Myers. I am a physician by training. And I would like your listeners to know that I consider myself a hopeless Grand Canyon addict. Pretty much love everything Grand Canyon and probably a lot like them and, the reason they're tuned into this podcast. Doug: OK why become a physician? Dr. Myers: I'd like to preface that answer by saying I'm a Mamma 's boy. I always have been. My mother is still alive by the way. She's 92 years old. My mother raised myself and my siblings on her own. It was very difficult and I have a tremendous amount of respect and admiration for her. My mom had careers picked out a professions for all of us, my siblings and myself. Like lawyer or doctor or banker but the two she seemed to hold in highest regard were priests and doctors. And she's very devout Catholic so she loved priests. But she also loved doctors and she would say “I have seven sons. One of you needs to be a priest. And one of you to be a doctor.” I remember thinking a priest? That ain't happening at least not with me you know girls are way too fascinating. You know I'm I might want one someday I did want one someday. I thought let Dave or Terry or Jim or John or Joe or Jerry have that priest job. And I'll I'll be a doctor. Anyway, she planted the seed. I didn't want to disappoint didn't want to disappoint her. She also told me that, you know, medicine was a noble career and a path out of poverty. And we were a welfare families so that also had an impact and that's why I started down the road to be a Doctor. Doug: OK. What Grand Canyon pictures or art or memorabilia do you have on your wall at home or at your medical office and tell me about some of those and why they speak to you? Dr. Myers: Most of the ones that we have on the walls at my house and there are a lot of them and memorabilia are things of photos that I collected with my adventures and explorations in the Canyon with my family. You know the ones that were there where where I was there with the ones I love most in my life. You know whether it's down at Phantom or somewhere remote those are the ones I cherish. And so a lot of those fortunately Becky hasn't been too annoyed that I put Canyon stuff up everywhere. Besides photos that take me back to a place in time and a memory, because really for me it's about the memories not the miles, but besides those that we have quite a collection of old Canyon signs they're ones that were hand routered. I had a friend that when I working on the South rim as a doctor the same time I was there the guy who has had the sign shop I went to high school with him and he was a buddy and I just asked him “hey do you have any old signs that are now obsolete that you're getting rid of?” “I guess sure Tom you can have this or that” and so I got some of those. But one of my favorites, it's kind of a cool story, but before they built the mile and a half rest houses there used to be a sign down at Havasupai Garden that said: last toilets until South Rim. So you're hiking up it's like you need do you needed to know you needed to use the restroom before you start it out because that was the last toilet for four and a half miles until you got to the rim. So when that was built, the mile and a half rests houses, that sign became obsolete. And I saw it in the trash pile with my friend who was the Ranger down there at the Garden at Time and I said “hey what you do with that?” He said “probably burn it. You know it's gonna be thrown away.” I'm like “can I have it?” He said “sure.” So I hiked it out and put it in the bathroom in our house at the South Rim. And within a few days of doing that, Robert Arnberger, who is a Superintendent and his wife Alvira, came over for dinner. And Rob said “hey I need to use the rest room.” “Yeah, sure, go ahead, it’s right over there.” And then Becky I looked at each other and went “uh oh, that sign’s in there.” And I thought “oh man, he might think I stole it.” And then he came out and he was laughing cause he knew the sign was obsolete and he was like “God I just love that sign.” So that's one of my favorite. Doug: OK cool. Now often physicians they specialize in a certain part of a medicine you know internal medicine cardiology whatnot. Why didn't you specialize? Dr Myers: Well you know honestly Doug I think an even better question from my perspective was: why stayed in medicine at all? And when I get to into medical school I got to be you know completely honest I was disenchanted with the career. I wasn't sure I wanted it to be a doctor. Ranger Doug: Why is that? Dr. Myers: Well, you know, the whole process was grueling you know it's all consuming you know it's really disheartening a lot of ways. The pressure was tremendous. You'd ask me one point about a mentorship and I'll talk about that but I didn't find ... I didn't have a mentor physician within that training somebody that I really aspired to be like. And so when I got to my senior year I told Becky “I don't want to do this. I don't think I'm very good at it as a matter of fact I think I'm probably suck at it, you know” and I said “I'd like to leave.” And she said “well I’ll support you whatever you want to do.” But that being said I also knew then I spent years and years and you know thousands of hours and a lot of money toward that career. And I would have a debt, my school debt, to pay off. And I decided to do my internship and just kind of see what happened. And I was in internal medicine. I got to the end of that year and I told the director I’m still searching for you know, for some place in the field. I wasn't really convinced that it was my path in life. And I told the director “I was leaving the program.” He said “wow, well what are you going to do?” And I said “I think I'm going to go to the Grand Canyon.” And he looks at me he goes, “What are you Myers, some kind of dirt farmer?” And I'm like: “No.” And he goes: “Well what would you do at the Grand Canyon?” And I said: “I'm thinking about being an interpretive Ranger.” He goes: “really”, he goes “what does that mean? You gonna give a Smokey the Bear enemas?” And I'm like: “no, an interp.ranger tells stories and educates the public about the place.” And I said: “That's what I think I might want to do as well.” “Good luck.” Long story short, I did eventually get my license to practice medicine, and I think Grand Canyon sort of found me. But that's a whole another story. But I ended up there and found out that yeah I really had a place in medicine. And it was in primary care as a general practice doctor. Just kind of a Jack of all trades which actually appealed to me in a lot of ways because I could see and diagnose and treat a lot of things and not I wasn't sort of focused in on one specialty. Doug: OK and you mentioned in your book about a mentor. Talk about having a mentor in your professional life and what's the value of having such a mentor? Dr. Myers: I think having a mentor really can't you know the value of it can't be overestimated. In my case at least mine was a guy named Jim his name was Jim Wurgler. He was a physician. He's the same age as my father. He came to Grand Canyon clinic in the late 80s after 20 years of being a physician in Yosemite National Park. So meeting him, the impression I have from the very get go was like oh this is the guy I haven't had all through medical school or even residency this is the guy I needed. Because he was he was so humble. He wasn't like an urban physician. His goals weren't to go play golf or you know have cocktails at the you know some high high end restaurant and nice meals and all that. He loved wild places. He loved the outdoors. He liked being a Jack of all trades when it came to medicine. You know, he could set fractures he could you know, do well child exams. Could treat heart attacks. He could do it all. But he was really kind and really humble. He's the best doctor I've ever known. And he took me under his wing and he taught me how to be a good physician. I don't think I'll ever …I've never been as good as doctor Wurgler. But I just, you know, cherish the time with him. I cherished learning from him and his passion for medicine. And he and I were on call. We split call every other night for emergencies. It was tough you know 24/7 you know 365 days a year. To handle all the after hour emergencies. And you know with doctor Wurgler though I knew because he was older than me, that the my days with him were limited. So I did cherish them. And some of my favorite memories, one of my favorite, actually at the end of the day, especially when we were so busy in the 90s with all those emergencies, Doctor Wurgler, who went by J-dub. You know J-dub would sit down his pen and he'd stare out the window, kind of looked longingly out in the distance. And say: “well Tom, so ends another hell day in paradise.” (Chuckles) And I'll never forget doctor Wurgler. He passed away several years ago but you know, if it wasn't for his mentorship I would have not had the career I've had at Grand Canyon. Ranger Doug: oh. That's great. Dr. Myers: Yeah I went to Grand Canyon because of doctor Wurgler. It wasn't because of the Canyon. I met him I went: “I went to work with that guy.” Ranger Doug: Well later on, you did kind of specialize in heat related issues. Can you talk about that a little bit? Dr. Myers: Yeah you know I think that uh, my understanding is he is not you know I I have a special interest in it. My goal was to understand it. You know and then use what I learned for prevention … to prevent heat related morbidity, mortality, with our visitors. You know and anybody. The single biggest motivation for learning about heat was the death of a 10-year-old hiker that I was involved with or you know had to try to treat. He died from heat stroke. His name was Phillip Grim. This was his tragic death occurred in July of 1996. His well-intentioned grandma and great uncle hiked him down the South Kaibab to Phantom. Yeah and what turned out to be the hottest day of the year. It was 116 degrees that day. Uh. Unfortunately you know he went into heat stroke down down at the bottom of the Canyon and he died within you know, 50 yards of Bright Angel Creek and 100 yards of the river. He still died from heatstroke. And he was flown out and we ran a full life support treatment up there and but couldn't he couldn't be resuscitated. And calling that code, it was it was you know, his death was one of the saddest moments of my career. And even sadder was speaking to his mother afterward. And talking to his grandma and great uncle. It was just tragic as mom told me that “it just tore my world apart” you know. And I thought to myself, it's like, “no one should die this way in the Grand Canyon especially a child.” You know so that's when I decided to try to make a difference about trying to prevent such deaths in the future and understanding heat illness and the nuances of it was part of that. And then educating people from what I've learned. Doug: So what changes have you seen in park medical problems over the years? Dr. Myers: Yes. There's an old saying you know within the Park Service and the EMS world that there's no new accidents it's just new faces, it's the same old accidents. One thing is, so there's a lot of trends in in certain areas that we will always have I think here. Fatalities or you know people will suffer you know morbid morbidity and mortality like heat illness, falls. The trend or the change that I see that's different from when I started almost 40 years ago is an older population like baby boomers. And people who are have Grand Canyon adventuring like hiking or river running on their bucket list. And they're really past their prime. And a lot of these folks, they overestimate their ability and they underestimate underestimate the wilderness, but they're really intent on trying to do this this one goal you know that's one last hurrah while they still can. And so we're seeing I think a little bit of an older shift in older population who are, suffering, you know, some of these issues of like say heat related death or cardiac arrest because they're they're pushing the envelope at an older age. Doug: OK. So you did write a 600 page book, co-authored that, about death in the Grand Canyon. You know, this seems like kind of a morbid subject. So why write such a book? Dr. Myers: Well you know I think that when you say it is a morbid subject, I mean that's absolutely true. It it is morbid but that said it's equally true that most of us if we're honest will admit that we have a morbid fascination with death. I mean you look at Internet or TV or movies or other book books, death sells! It always has but there's a lot to be learned from death. You know it's been through studies on morbidity mortality that you know we have seatbelts and car seats for infants and children and life jackets and motorcycle helmets you know et cetera. Yeah in order to teach somebody, and then order to teach somebody something in the area where fatalities have occurred, you have to get their attention first. And so if a tragic accident is presented, say one that there's a sequence of poor decision making that's somewhat compelling to find out you know what led him into this ultimate fatal outcome, you know, if there's a sequence of that and it and it triggers the person 's curiosity and that even if it's morbid of a curiosity, that when you hold their attention in that moment, then you slip in a lifesaving lesson you know about what could be done to prevent a future fatality. And repeat someone dying the same way as the person you just presented. So that's the whole point of it of this book is tell us you know a a story one of morbid curiosity a tragic death perhaps but then slip in the life saving lesson when you have someone 's attention. Doug: OK. What, co-writing book 600 pages got to be a monumental undertaking. What are you most proud of about this book? Dr., Myers: Well I I can say without a doubt I'm most proud of the tragedies that haven't occurred because of it you know the ones that you'll never read about or I'll never read about or no one will hear about because someone made an informed decision, a lifesaving one, say by not hiking at the hottest time of the day or the hottest time of the year because they read the book. You know for what it's worth I've been told that more times than I can remember about people who said “hey I changed my plans from potentially lethal ones to see maybe life sparing one because I read your book. I knew that this was a bad time to hike and I learned that from your book and I just want to say thanks.” And so you'll never read about them in there and I'm really proud of that. You can't measure a catastrophe that didn't happen or disaster that didn't happen. But you know I know there's definitely some people out there that didn't end up the book because they read it. Ranger Doug: OK well done. Now in your latest book you write about a memorable medical save of an infant. And I don't want to reveal that here the readers can read about that but I'm sure you've had other important medical saves, with air quotes, in your career. And so without violating any HIPAA laws, maybe tell us 2 or 3 of medical saves that you are particularly proud of. Dr. Myers: Sure. The one that stands out was shortly after I got out my internship and I I started working in the Williams healthcare center, a sister clinic to Grand Canyon. Before I was hired about 2 weeks later to work at Grand Canyon, I was I was there in Williams. And we got a call from the medical dispatcher that they were going to bring in some patients from a rollover accident on Interstate 40. So it was an MVA. And supposing that in this accident I could hear the nurse talking to this dispatcher about what happened it it was. She said “well yeah, seven people were involved in this accident, roll over, two were ejected. Those two are in critical condition. One of them would need what they call a crike, a crike with cricothyroidotomy, an emergency airway procedure because they had so much facial trauma they the medics couldn't get an airway tube through the mouth into the throat. And I remember talking to her and she had the phone said “hey doctor Meyer as well, you need to know this they're bringing in seven patients our way our way two are in critical condition one needs to crike because of this airway issue.” And I'm like, “what? Norma that's like that's level one trauma, you know they need a trauma surgeon they need an anesthesiologist why they come in here?” And said: “well it's raining’ (it was raining cats and dogs and that's part of the reason that this van rolled over. It hydroplaned and and then rolled). And to get to Flagstaff even by ground ambulance so still probably an hour in that rain to get to the hospital and they couldn't fly him so they couldn't ground can fly and they didn't have an airway an airway is critical you know for oxygenation for the blood I mean for the brain you know for the heart you know all of our organ systems and so I told her I said her name was Norma the nurse I said “Norma, I've only done one cricothyroidotomy, one crick in my life and it was on a on a dog and it was part of our dog lab we learned procedures.” And she said: “well doctor Myers, you won't be able to say that in about 2 minutes you know.” And so, sure enough, they brought this patient in, a lot of trauma and I went ahead and did this procedure to get the airway into the the throat and you know it worked and we were able to send that patient out still alive. Another one that I remember that I'm particularly proud of, and think think of with with fond memories, was a hiker on the Tanner Trail in the early 1990s. Got a call it was after hours they were flying a guy out that was, he had excruciating abdominal pain and he was weak and numb from the waist down and really couldn't walk. And so I remember going to the clinic and seeing this guy who was I think in his early 40s or middle 40s at the time and he was kind of writhing because he had a severe abdominal pain. And the abdominal pain when did exam I found was you know very distended bladder. Unfortunately he was he had gotten progressively weak in this hike and then to the point where he started stumbling. Then he couldn't stand at all. And then he was unable to urinate. And on his exam he had a very distended bladder. He had with they called a neurogenic bladder. It wouldn't allow him to to urinate. So we had to place a Foley catheter into his bladder which when his bladder was empty the abdominal pain went away. But on his exam he basically had paralysis from his waist down. It was a very critical situation and got on the phone and immediately flew him to Barrows Neurological Institute in Phoenix where they had neurosurgeons on call. And you know I had to look it up actually I I knew it was serious and it was his history and condition was consistent what they call a Cauda Equina Syndrome, cauda equina lower part of the spinal cord. And something was happening there was putting pressure on that area and he was going paralyzed. And so flew him down there he was taken to emergency surgery. I knew he got through the surgery fine, but then he was lost in follow up. Ranger Doug: What does that mean, lost in follow up? Dr. Myers: Oh you know, I never heard from him again. I sent him there and then the care was transferred and so I had no, and at that point, you know, we didn't have cell phones. I didn't have access to trying to call them and find out how things were going. But about 20 years later, I had a phone call, a number that was referred to me, about a guy who wanted to speak to this doctor that saved his life supposedly. And he was looking for a doctor named Michael something and and I didn't know the name of Michael. I I talked to doctor Wurgler, my mentor, and I said “hey do you remember anybody that was working in the clinic then in the 90s that might have seen this guy?” Because we had resident doctors coming through and he didn't remember him. And I said: “OK, well.” I called the guy and and started talking to him. And he started telling me the story he said you know “it was really I was really worried I was really scared you know and we I had to flash a jet with a a mirror you know to get attention and they made the calls that was routed over ultimately to Grand National Park in the park.” And the park flew in and got him. But it was a mirror flash. And he said: “I was so concerned you know and I I thought I was gonna die and I you know, and I saw this doctor and he I told him what was happening.” I go and he said; “I was starting to go numb. I go: “oh let me finish this story.” And I told him that and he goes: “yeah” he goes: “you know it.” And I go: “yeah the Doctor you saw was me.” Ranger Doug: Oh wow! And he said “I just wanted to tell you, I thank you for saving my life.” I said: “well it wasn't your life but it was your spinal cord. And he had a he had a bleeding into his spinal column and was putting pressure on his lower spinal cord and that's why he was going paralyzed. And it could have become life threatening but certainly at that point you know it threatened paralysis. Ranger Doug; So how did he come out from the surgery? Dr. Myers: Really really well from what he told me he only had partial weakness and numbness in one leg but otherwise was able to walk and you know almost a complete recovery. And that was really gratifying all those years later that he tried to track me down, so. Ranger Doug: Wow Oh well well done on that I'm sure there was very satisfying. Dr. Myers: Thanks. It was. Ranger Doug: You got a new book out called the The Grandest Trek. Subtitle: Unforgettable people stories and lessons from life and from hiking length of the Grand Canyon. Now 400 pages storytelling sharing the lives and motivations of some really elite Grand Canyon hikers. These are kind of super hiker folks that route find. They pre-place resupply caches with water and food. And they hike mostly off trail through the length, end-to-end of the Grand Canyon, trek you know some 600 miles. Maybe only 60 odd individuals have accomplished this hike, this task, in modern times. I loved that the book is also as you advertise it, a love story about you and your family. You completed the hiking trek. Took you seven and a half years, 16 different, what are called “section hikes” kind of linking it all together. Sixty-odd hiking days, 600+ Grand Canyon miles, you know, not an easy accomplishment. So well done on just accomplishing that. On Page three of the book and you say this book is in fact a love story which I completely agree with. So without revealing any surprise endings to your stories please tell the listeners, a little bit some of the hikers you profiled and why you chose them. Dr. Myers: Well, I chose the ones I did because I didn't want their unique stories and their special legacies to be lost to the sand time. Honestly that that was really important to me. I wanted to honor them and document their tales as hiking greats. And I wanted to document that part of our hiking heritage before it was too late. I always felt like with hiking the Grand Canyon there was a rich legacy as rich as river runners. You know river runners in in lot of literature there was so much out there on John Wesley Powell and Georgie White. There was a lot of stuff written on river runners but for the hiking community we just didn't have much but I knew there was a rich legacy there. And I wanted to get that documented. So choosing Kenton Grua. who was the first person known to have hiked the length, was a no brainer. I really wanted to tell a story. He was someone I knew well and that he had what I think may be the greatest love affair with the Grand Canyon that anyone has ever had. More than anybody I know. George Steck was another guy that I really wanted to highlight. He was a hiking mentor of mine and a father figure. He wrote 2 books Grand Canyon Loop, Hikes One and Two. And he's considered the godfather of lengthwise hiking. He was a genius, he was brilliant. But he also had his playful and mischievous side. And he loved Grand Canyon about about as much as Kenton or as anybody could. And I want George, his legacy legacy to be out there. As far as everybody else it was it was similar you know that these are special people. These are hiking greats. These people, you know they should shouldn't be forgotten. And so that was a big motivation. I also wanted to get in their heads you know and that's so much a you know how they did it or when they did it but the who they were and the why that they did it. That was really important to me. Ranger Doug: Do you uh do you want to read the book dedication. Do you have that? Dr. Myers: Uh let's see: all proceeds from the sale of this book will be donated to the Grand Canyon Conservancy in the memory of Robert Eschebenson, one of the Grand Canyon 's greatest hikers. Ranger Doug: So why him and why the Grand Canyon Conservancy? Dr. Myers: Well I'll start with the Conservancy which was founded in 1932. I'm a lifetime member. I joined when it was the Grand Canyon Natural History Association. But the Conservancy is the parks official philanthropic and collaborative partner. You know I make the I'm making the donation to the Conservancy I I do in the hopes that the healing powers of the Canyon which the Conservancy has done so much to support over the years, will touch the life of someone in need. Someone like Robert Benson. You know that's that's really and for Robert if you want I could tell you you know who he was and it kind of thought giving. All of it away. Ranger Doug: Yeah there's a good surprise ending about him true. Dr. Myers: Yeah there is. But you know he he was just an astounding hiker. And I love the fact that he loved Canyon Country so much and would seek it out for adventure for you know, solace, for self-worth, for so many reasons. But a very unique man. I wish I could have met him. I never did. I would love to have talked to him but it's nice to I think it's nice to honor him in the book and you know have the proceeds done it in his name and so that his legacy will live on. His life was far too short but I want his legacy to live on. Ranger Doug: Well well well well done and you have an opening quote you want To read that. Dr. Myers: Oh sure sometime it's on the path it's on the path most rocky that you will find your footing most true. Ranger Doug: So tell me about that. Dr. Myers: Well it's obviously a metaphor. It's one for life. I think it's tempting and far easier to choose a path of least resistance in life. But sometimes that path less traveled, you know the one that you know the the path that's less traveled you know the the one that's far more difficult and rocky, say like hiking in the Grand Canyon, but it's that path that difficult one that will take you to a destination that leaves you more fulfilled. For me it was medicine you know and I I liken that journey to a hiking the Grand Canyon. It was very very hard you know and you start off enthusiastic and excited but the going gets rough immediately, especially going off trail. And often you feel you know that you're just way in over your head. You're confronted with terrifying exposure. Your, the landscape you feel abused by it and you know wears you out. But, you know you keep going and going. And sometimes you're convinced you're completely on the wrong path, you know you keep going and going and just like in the Grand Canyon, like a medicine the further you go the harder it is to turn around. You know and but You you you hope and pray that the destination will be worth the journey and sometimes it is on that rocky path that you're going to get to that destination you're going to feel mostly you're going to feel more fulfilled. And you look back and you go: “that footing was true to me because I was being true to myself by taking that path.” Now about that kind of taking the path like that I'm going to say you know a lot of us you know the path is chosen for you. I mean people who endure horrible things in medicine you know that's not a path they wanted or you know sometimes a setback. Say what you were born into. Poverty. An abusive family. That's not the path that you wanted. But you know it's it's what you have to deal with it might be terrible almost unbearable. It's not the one you wanted but it's what you got. And now it's up to you to try to navigate and do something with it. You know as far as that line Doug I I first came up with it about 20 years ago. And I put it up … I put it into a letter that I wrote my daughter when she was going going off to college. And I and I have an excerpt of the rest of another phrase a little more of that letter. Where that phrase was used I can share it with you if I want I have it here? Ranger Doug: Sure go ahead. Dr. Myers: So I told her I said her name is Alexandra she's my middle daughter: Follow your heart but allow wisdom and experience your own and that of others to guide you. Let enlightenment that from within and that of the divine, inspire you. Live the life you choose to the fullest. Strive to leave nothing on the table of regret. Use determination and strength to carry you to your goals. Make honor integrity steer your footfalls, not fear. But courage and but courage light your your way and remember sometimes it's on the path most rocky that you will find your footing most true. But it won't always be rocky. It won't. And there will be plenty of flowers along the way. Never forget to stop and smell them. Ranger Doug: Wow. Well done. Book authors labor long and hard to craft a finished product. Please pick out two or three of your favorite written passages if you would. Please read them and tell us why you're especially proud of them. Dr. Myers: OK. Sure. In my introduction where I mentioned that the book is love story as you said, I speak to what I call dancing lessons. Meaning that hiking and exploring the Canyon on foot is somewhat of a dance. And the ending passage of my introduction my dancing lessons goes like this: As love stories often do this book includes thrills as well as laughter and delight. Some moments worthy of dancing and leaping. Yet they're also times of anger fear intense sorrow and heartbreak. Taken together it's a heady mix of lessons for life learned in one of the most spectacular dance floors on earth. And while the Grand Canyon clearly rewards efforts made to learn the steps and rhythms, Mother Nature serves up here is just as clear that is a place where bad decisions or bad luck can end the dance forever if the steps are worth it. Though some have suffered grieve and even lost themselves in the stance, far more including me have rejoiced in being found. So I really like that I feel like it captures my feelings about, you know, learning the steps and rhythms and, you know, how to dance in the place like the Grand Canyon. So I felt that was something I'm proud of how I articulated in. Ranger Doug: OK. Do you have another one Dr. Myers: I do. This other line occurs where I mentioned how I loved Kenton Grua. Again the the first man to walk the length of, a friend of mine. And in a particular chapter remark about how much he loved this place the Grand Canyon which was something we shared. So the next line I say after that it it's just one of my favorites, is this: For seekers of beauty solitude and adventure within Canyon country there is none greater. The Grand Canyon, with its Colorado River, is the earth 's glory hole … the geologic jackpot and lithic Nirvana. Ranger Doug: Wow. Dr. Myers: For me that's what it is. I mean I think it's I think it's the glory hole. I think it's it doesn't get any better than this especially for Canyon Country. It is it's the it's the you know the big enchilada. The cat's meow et cetera et cetera. Ranger Doug: OK yeah those are all under statements when you stand on the rim and look at the Grand Canyon. Dr. Myers: Yeah. Ranger Doug: Anymore? Dr. Myers: Well those the ones I came up with. Ranger Doug: OK why I got one for you a question you know. We are an international dark sky National Park. Grand Canyon is. And we regularly have visiting and resident astronomers to the park. They share their love of the dark skies. And I like to make them stop and ponder when I ask them this question: “What is more impressive to you while you're at the Grand Canyon? Looking down? Or Looking up? And for you I'd like to kind of tweak this question a little bit, uh, because I know below the rim there are places where a visitor can actually look straight ahead and enjoy awesome views. I'm thinking of maybe the Tonto Platform and out on the Escalade area, which I've never been before. So here's my question to you: Please share with me a couple of your favorite places within Grand Canyon National Park for: looking down? Looking up? And looking straight ahead? And why did you pick those locations? Dr. Myers: Hmm. Well. They’re tough. You know, it's kind of like a trying to asked me to pick my favorite child of my three, which I love them all the same. But, there's so many potential answers. Ranger Doug: Like just shoot me some that come off your head. Dr. Myers: There are. You know, like you I I think I would say my overall favorite views are from on the Tonto Platform, or down inside. Because, if you're on the Tonto, say midway, you can look down into you know the inner gorge. And it's spectacular. I think your your your reference your frame of reference is a little bit better because you're so close to these huge drop offs which are sometimes spectacular. And you can look up toward the rim so you get both of those, you know, kind of very front and center. But I would say say looking down from the rim country the Cape Solitude area in eastern Grand Canyon kind of the Navajo reservation side it's kind of just a little bit out from the Desert View area which I love that those views but over there the the river snakes out into the distance you know far below you and it's just spectacular how it winds over there. And then the buttes seem to just loom you know like Chuar. It's just amazing. And then you have this jagged outline of the the Palisades of the Desert you know just this picket fence sort of formation. And then looking upstream you have views into Marble Canyon and the Marble Plateau and then the Painted Desert way out there. So it's breathtaking to me. Those are one of my those are one of my all time favorites I will say also as far as rim views here at the North Rim like say Cape Royal and looking way to the South and to the Canyon and then out in the distance see the San Francisco peaks or you see Bill Williams Mountain you can see Red Butte I mean it's just it's spectacular as well. I love the views from the North Rim. Them looking up you know one of my favorites is from the river when you're below Comanche Point and on the river you look up at it. It just towers and it's very pointy and it looks like it's separated from the rim it's actually not but it looks like the Matterhorn. And it's just this huge promontory and it's spectacularly beautiful. I love that view from looking up. Looking straight ahead in the sprawling Esplanade in western Grand Canyon you mentioned that and that's that's the Grand Canyon is a Big Sky country. I mean you just feel extra small there and and it's good for perspective on you know, you and your life. For me I just love the view of the Esplanade it stretches forever. Other areas I would like to look straight ahead are where if you're on the river, and there's the river is wall to wall so there's no shoreline it's wall to wall like the Red Wall gorge or upper upper and Middle Granite Gorge or the Muav Gorge, you know, it's just I love those views. Where you just have these these towers like the the Kliston Tower like Muav Gorge, 1200 feet high. And you know they just they just loom and it's those those are spectacular and you know. So why did they pick those? You know some of it depends on relative remoteness and how hard it is to get there in the mood at the time, I you know, I'm picking place that a lot of people haven't seen. The river? Yes. But some of the other areas a lot have a lot of people haven't seen them. So that said though you know a lot of the areas on the South Rim village area here in the North Rim, they're equally spectacular you know there's so many but those are some of my favorites. Ranger Doug: OK. On page 205 you write about a female patient of yours. Can you please read the entry. Dr. Myers: Sure. I never fully appreciate the incredible power of dependency until it's a patient with emphysema, AKA COPD, explained it to me. Despite experiencing what equates to slow motion suffocation she was hopelessly addicted to nicotine and continued to smoke. Early into the visit I had reflexively rattled off in standard doctor's speak “you need to quit smoking.” With tears in her eyes her gaze earnest, she sniffled. “Doctor, you don't understand. Cigarettes are my friend. Unlike people in my life, they've always been there when I need them most during stressful times. And they never judge me.” She told me she got hooked on cigarettes as a teenager. Instead of a snarky “well with friends like that you'll never need an enemy,” I stayed silent. Digesting what she said. And made an impact. In that empathetic moment with singular gratitude I thought of one of my own best friends. Ranger Doug: Can you stop there? Please bear with me let me set up a scenario for you. You are in a therapy group for addiction. I am the group facilitator uh can you play along with me? Dr. Myers: Of course. Ranger Doug: OK. “Now Tom I see you've been coming to the last few group therapy sessions. You really haven't said much instead you have sat quietly through our sessions. I think it is your time to speak now. I would like for you to please stand state your name and talk about your addiction. It may not be a true addiction. That's OK. Maybe you can call it one of your own best friends. Whatever. Explore how this best friend addiction makes you feel and what does having this best friend addiction mean to you. Dr. Myers: OK Ranger Doug: Please rise. Dr. Myers: Alright standing up. Hello my name is Tom Myers. I have a hopeless addiction to spending time with my good friend the Grand Canyon. This friend, one of my best, does not reciprocate the love I have for it. Nor does it care a wit for my well-being. But this friend gives me when I see it and spend time with it and explore it, this friendship, is a feeling of inspiration joy and euphoria as well as a sense of peace and contentment, I don't find anywhere else. At least not with this not the same level with similar friends and meaning similar landscapes. This sense of euphoria and inspiration is especially true when I hike it … the feel-good buzz I get from this friend after finishing a grueling hike is incredibly addicting. And it it just keeps me coming back for more and more to this very day. Yeah, like I can't get enough. Ha Ha! Ranger Doug: OK so that's your addiction? Dr. Myers: It is. Grand Canyon I mean. Yes. I believe people can be addicted to landscape I do in a in a healthy way. You know, they can be unhealthy if they take it to extremes, anything can be obviously. And I know for me you know there's been times where I've pushed it too much. But, you know, I I do feel like for the most part it's been something that's really been beneficial to my mind and body. Way more than harmful. Ranger Doug: OK well I have a magic wand in my hand. And I have two venues. And I have the power to bring back two people from the dead. Each has some connection to the Grand Canyon so. Here's the first scenario and venue. It's the north porch of the El Tovar hotel on the South rim. This is normally a seating area, but just for you, it is currently flagged off and closed with no public access or disturbances. A simple dinner table is set up in the middle at sunset time, two chairs, white tablecloth your own private servicer are standing to the side at the ready. I'm waving my magic wand and then invite, have invited anyone dead from the past to sit at your table for a private dinner conversation. The person must have a connection to the Grand Canyon. Here's your questions: What do you order? Who are you inviting as your dinner guest? And what do you want to talk about? Dr. Myers: Wow well I love that scenario. I love the venue that's this is terrific. So my order would start with the French onion soup at El Tovar which I think is great. It's topped with shredded Swiss cheese and croutons. And then my entree would be a Navajo Taco. Yes. And my dinner guest would be … Teddy Roosevelt, Theodore Roosevelt. I would order the same for him. You know, my treat. Unless you're paying for it I guess. Anyway, with your wand you'll pay for it. After dinner I would order mint juleps for each of us. I knew he liked those or I know. And then I would ask him the conversation I would ask him about his that first impression he had of the Grand Canyon where he famously said leave it leave it as it is. Man can only mar it. That was incredibly forward thinking. You know in my mind especially in the era where wild places were to be conquered. Untamed and natural resources exploited for profit and development. Then I would take my glass that mint julep, and I would toast him in a moment. and I would thank him for inspiring that the groundwork for the ultimate protection of the Canyon and leading leading a call for it to become a National Park. Because he did that 1903 almost 20 years before it became a part you. Know that better in me. And then I'd sit back and listen to TR tell stories. Like mountain lion hunting on the North Rim with Uncle Jimmy Owens. Or running cattle on the Badlands. Or rushing the San Juan Hill with Rough Riders. Or hunting on the Nile. And being President you know so many things I would just sit back and listen. That would be great. Ranger Doug: I have a a new setting for you … a second setting. It's down the bottom of the Grand Canyon. It's a beautiful October day, eight PM. Dinner’s done. Sun is already set. There is a quarter moon up. Its casting a moonlight onto a nearby Cliff although none directly on your camp beach area where you're sitting. There are two camp chairs set up on a beautiful Grand Canyon sandy beach. There's no wind. A small campfires going on the fire pan. You are alone with your guest. What post-meal drink do you have in your hand? And who would you like to bring back from the dead for your conversation? Who is that person and what would you talk about? Dr. Myers: Wow I love that setting even more than the El Tovar, especially the no wind and all that kind of happening it's like that sounds like just pure fantasy. Super. So in my hand would be a shot glass and it would be filled with Hayner whiskey and whiskey from, you know, the 19th century. And next to me would be John Wesley Powell. I honestly think it would be almost sacrilegious to see anyone else especially for an historian. And as for that conversation, you know like that with TR with Roosevelt I would just listen for the most part. But I would start with a question that comes from being a doctor. First I would ask him about the loss of his arm and the battle of Shiloh. You know how was it injured? His impression of the injury at the time and then ultimately having to have it amputated. You know did he get any chloroform or any kind of sedative? Did he literally have to bite the bullet and take the pain when they saw it off the jagged end and tried to make a stump? I I would really like to hear about that. Because that, you know, I I know it's horrific for so many. I once saw a bullet that somebody bit so hard in this is from the Civil Wars out of battlefield and we went to, and his tooth came out in the bullet and it was on display. Ranger Doug: Oh, jeez. Dr. Myers: Then I would ask Powell about his exploratory descent of the Colorado in 1869. And part of the reason I want to talk to Powell is specifically, I would ask him about his relationship with his men. His impression of them and then vice versa. And I would ask Powell to then, walk me through the incident at Separation Canyon where three of his men Oramel and Seneca Howland as well as William Dunn, left the trip and were never seen again. You know that that happened at a place that's now called Separation Canyon. So what really made them go you know as far as Powell saw it? Were they really scared of the river, or did personal tensions between him and them, play a role? You know that's been a very controversial topic ever since and I'd love to hear it from the man you know directly you know what actually happened you know Mister Powell? Yeah. Ranger Doug: OK. OK well when you get that answer be sure to share it with the rest of the world. Dr. Myers: Absolutely. Ranger Doug: OK I'm kind of on a roll here with my magic wand so I have a final scenario for you. You get to pick your special place at the Grand Canyon for your celebration of life while you're still alive. I can wave my wand I can bring back friends, families from anywhere including from the spirit world and beyond for your grand gathering. I'll magically transport everybody to your select location. All will rise raise their glasses and toast your life. Tell tall tales. Laugh. Cry. Maybe sing a song or two. All will enjoy coming together. Please describe the Grand Canyon location you choose for your grand gathering. Dr. Myers: Well I have to say you're great Doug you're alright I just love these questions. These are so awesome, so creative. Thank you. So for me there you know so many wonderful and spectacular spots but I think my grand gathering would be at Phantom. And that's really where it all began for me. From feeling my heart and soul captured by the place you know during my first hike there when I was 19. My first overnight stay there when I was 19. And then the unforgettable and magical moment of taking my wife, my fiancée Becky down there for the first time. And then taking my kids down there for the first time when they were infants and toddlers. And all the and then hopefully my grandkids we're going to do that hopefully this year but and then all these magical moments I've had down there especially in New Year's to celebrate New Years has been a tradition for me. So going almost 50 years and I've done it with, you know, my family and close friends. And so Phantom will always have a special place in my heart more than anywhere else. So that's where I want my my grand gathering to be. Ranger Doug: OK and what are the 3 things that you're most proud of in your life that you want your family friends to mention and acknowledge at your grand gathering at Phantom Ranch? Dr. Myers: So that fits into what I've frequently called and done this for a long time headstone goals. That's something I've talked to my kids about and I think it's important to to intentionally live your life to fulfill those goals. So what is a headstone goal? By that I mean it's like what's your life’s legacy. If you were to capture your life legacy on a headstone, what would what would be said? What would what would you want written on there? How would you want to be remembered and how it would and would it reflect reflect the reality of how you lived? So for me you know there would be several tiers on that headstone. The top tier would say he was a good husband it would say Tom Myers, he was a good husband and father. Equal billing. You know that's where most proud of I think I've been a good husband and a good father. And that means more to me than anything. The second tier would say he was a good son. He was a good brother. And he was a good friend. Those are really important to me as well. Third tier was, he was a good doctor. He was kind. He was caring. And he really wanted the best for every patient he saw. And I believe that's true. And lastly, he was a decent historian and a reasonably good writer. So that's that. Ranger Doug; Not not a bad legacy to leave behind! Dr. Myers: Thanks Ranger Doug: it's been great chatting with you and I do have a present for you here. Since you are a book author. I can't match that but we do have a few parody songs here at …the North Rim of Grand Canyon so here's a collection of our corniest, funest parody songs for you. Dr. Myers; Wow well this is great I look forward to like reading them and trying to sing them. And I have a gift for you you. It's a copy of Over the Edge. And I'm really proud to give it to you. And you know cherish this Grand Canyon parody songbook, Doug. Thank you so much. Ranger Doug: OK hey well great. Great agreeing to sit down and chat with us and we'll see you later. Dr. Myers: It’s been awesome. Thanks. Ranger Doug: This podcast, Let’s Meet Grand Canyon’s Doc, is brought to you from the interpretive team at the North Rim, Grand Canyon National Park. I’d like to gratefully acknowledge the Native peoples on whose ancestral homelands we gather, as well as the diverse and vibrant Native communities who make their park home here today. Thanks for ranger Leah for podcast editing. Wow. What an honor it was for me to sit down and share a conversation with Dr. Myers. He is such a fascinating person. I hope you found our Grand Canyon doc, Dr. Tom Myers, as an impressive a human being, as I did. Thank you, Dr. Myers, for taking time to share your experiences, thoughts and stories with us. As I wrap up this podcast, I am thinking to myself: what is the take-away from the podcast? What would make a really powerful ending? Then, I remembered the letter of advice Dr. Myers wrote to his daughter. I really like his father-to-daughter advice. I found it very wise. Even profound. Something maybe we all should consider. To ponder. If you want to re-listen to Dr. Myer’s advice, scroll back to around the 35-minute mark, and give it a second listen. Finally, I just finished read-reading Dr. Myers book: Over the Edge, Death in the Grand Canyon. There sure are a lot of ways to end up injured, incapacitated or otherwise in need of medical attention at the Grand Canyon. My hope is you have a safe visit to the park. I hope you never need to be seen at the South Rim’s medical clinic. I hope, even more so, you never become a statistic, and land in the Death in Grand Canyon book. Yes, there are some true Act of God causes to injuries, mishaps and death at Grand Canyon. Stuff can just happen. But there is a strong trend, identified in the Death book, as to many of those causes. This is the USA. It seems we are always looking for someone else to blame for our misfortunes. Maybe the Canyon Doc? Maybe a park ranger? If you are looking for someone to blame, I encourage you to listen to our ending song. Listen closely to the fun parody lyrics that ranger JD wrote for us. You will find the answer there. With apologies to Jimmy Buffett, I am ending this podcast with: Hiking Away Again at Grand Canyon. I am ranger Doug, thanks for listening. ♫Guitar and singing: Munching on trail mix, Getting my hike fix, All of those tourists crowding the rim. Checking my trail guide, This canyon is so wide, Making it hard to go rim to rim. Hiking away again in Grand Canyon, Searching for my elec-tro-lytes (salt, salt, salt), Some people claim, there’s a Ran-ger to blame, But I know, it’s my own darn fault. Don’t know the reason, I’m hiking this season, The lottery gave a permit I didn’t choose. But it’s a real doosie, A backcountry beauty, How I’ll do this route I haven’t a clue. Hiking away again in Grand Canyon, Searching for my elec-tro-lytes (salt, salt, salt), Some people claim, there’s a Ran-ger to blame, But I know, it’s my own darn fault. I blew out my hiking shoe, Stepped in some mule pooh, Blistered my heel, had to limp up the trail. All these crazy rim to rimmers, Soon will surrender, Realizing Grand Canyon, will always prevail Hiking away again in Grand Canyon, Searching for my elec-tro-lytes (salt, salt, salt), Some people claim, there’s a Ran-ger to blame, But I know, it’s my own darn fault.